In des Sees Wogenspiele

Fallen durch den Sonnenschein

Sterne, ach, gar viele, viele,

Flammend leuchtend stets hinein.

Wenn der Mensch zum See geworden,

In der Seele Wogenspiele

Fallen aus des Himmels Pforten

Sterne, ach, gar viele, viele.

Into the play of the waves on the lake

They are falling through the sunshine -

Stars, oh, so many, many of them,

Blazing, alight, endlessly falling.

If a human were to become a lake,

Into the play of the waves in the soul

Falling out of the gates of heaven there would be

Stars, oh, so many, many of them.

Bruchmann, Am See (D 746)

If a human being was a lake, stars would fall into the soul’s playful waters (In der Seele Wogenspiele). Notice the punning reflection of line 1: In des Sees Wogenspiel. The soul (Seele) sounds like a lake (See), so the poem plays with the metaphor that the soul is a receptacle filled with water. It can be moved and stirred. It is open to higher things. It has depth. The surface might play tricks on us, but underneath there is a more significant reality.

Other poets also used water imagery when they referred to the human soul, with the flow of rivers pointing to the restlessness of the human condition:

Ist mir's doch, als sei mein Leben

An den schönen Strom gebunden.

Hab ich Frohes nicht an seinem Ufer,

Und Betrübtes hier empfunden!

Ja du gleichest meiner Seele;

Manchmahl grün und glatt gestaltet;

Und zu Zeiten, herrschen Stürme,

Schäumend, unruhvoll, gefaltet.

Fließest zu dem fernen Meere,

Darfst allda nicht heimisch werden;

Mich drängt's auch in mildre Lande,

Finde nicht das Glück auf Erden.

But it appears to me as if my life

Is bound up with this beautiful river.

Is it not the case that on its banks I have known something of joy

And I have experienced distress here?

Yes, you are similar to my soul;

Sometimes green and with a smooth surface,

And at other times, when storms dominate,

Foaming, disturbed, furrowed.

You are flowing towards the distant sea,

Unable to feel that you belong anywhere.

I too am being driven to a more gentle land -

I cannot find happiness on earth.

Mayrhofer, Am Strome (D 539)

Des Menschen Seele

Gleicht dem Wasser.

Vom Himmel kommt es,

Zum Himmel steigt es,

Und wieder nieder

Zur Erde muss es,

Ewig wechselnd.

The human soul

Is similar to water:

It comes from the heavens,

It rises to the heavens

And back down

To earth it has to come,

Eternally changing.

Goethe, Gesang der Geister über den Wassern (D 484, D 538, D 705, D 714)

Many of the adjectives that modify the word ‘soul’ in Schubert song texts are related to this water imagery: storm-tossed (sturmbewegte Seele, D 516), troubled, pure (Die bedrängte, reine Seele, D 758). Others, though, centre on other ‘liquid’ metaphors such as the soul as a vessel (die volle Seele, her full soul, D 288) or intoxication (die wonnetrunkne Seele, my ecstasy-drunk soul, D 413).

Souls that are ‘full’, ‘drunk’ or ‘storm-tossed’, can also be depressed (Klage, D 415) or delighted (Zum Punsche, D 492). They can feel pain and anxiety (Pflicht und Liebe, D 467; In der Mitternacht, D 464). They can strive (Sehnsucht der Liebe, D 180) and they can move from darkness to light (Abendlied für die Entfernte, D 856).

In other words, in many of these poems the soul is not a single, unchanging reality, the sort of thing that can live on in eternity with no more development and no longer subject to the impact of normal life.

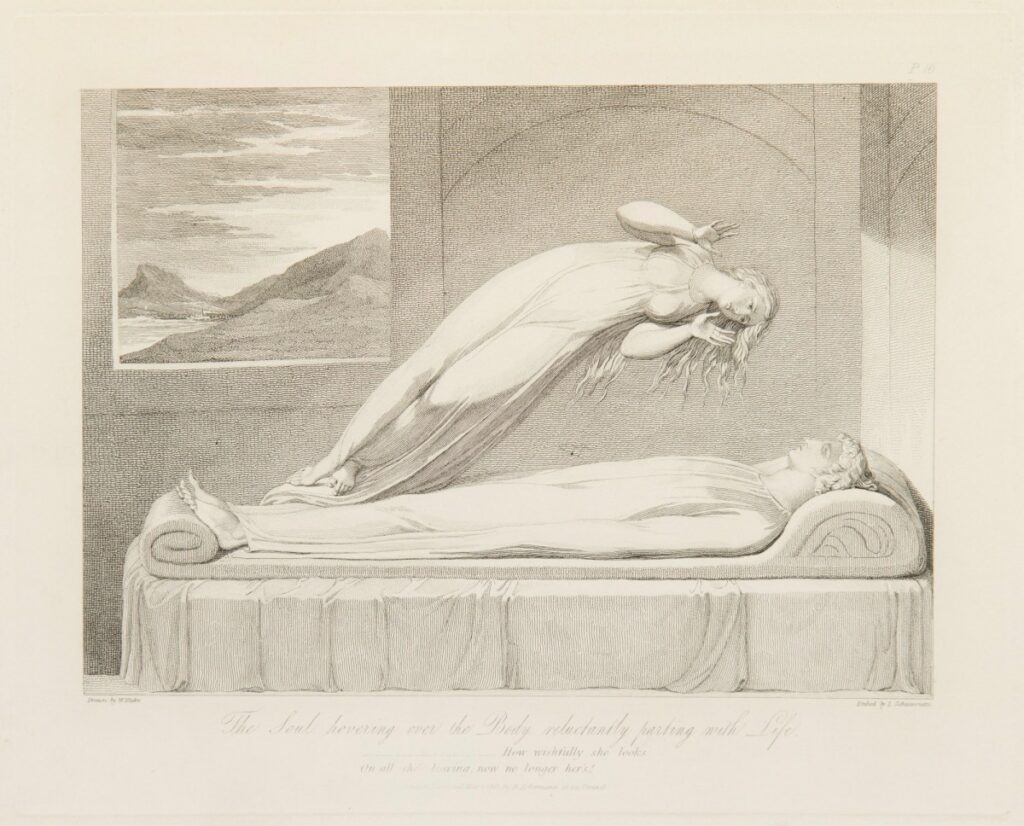

Of course, Schubert did set some ‘pious’ texts in which souls are either ‘released’ from the body at death (Die junge Nonne, D 828) or invited to ‘rest in peace’ (Am Tage Aller Seelen, D 343), but the major concern of the poets in these cases seemed to be to offer consolation to, or instil determination in, those who are still involved in the struggles of this life.

It is interesting to compare the young nun (D 828) who longs for her heavenly bridegroom to come and release her soul from its earthly prison with Goethe’s An den Mond (To the moon). Here the poet feels that the moonlight over the River Ilm is already releasing his soul:

Füllest wieder Busch und Tal

Still mit Nebelglanz,

Lösest endlich auch einmal

Meine Seele ganz;

Breitest über mein Gefild

Lindernd deinen Blick,

Wie des Freundes Auge mild

Über mein Geschick.

Once again you fill the woodland and valley

With a quiet, misty glow,

And in the end you also manage to release

My soul completely.

Over my realm you spread

Your soothing glance,

Like the gentle eyes of a friend

Watching over my fate.

Goethe, An den Mond (D 259, D 296)

Here, there is no need to wait for an afterlife in which a soul can find release or fulfilment.

Obviously, many love poems share this approach. The presence of the beloved already admits the poet’s soul into bliss. In many cases souls blend and merge.

So immer Seelenblick im Seelenblick

Auch den geheimsten Wunsch des Herzens sehen,

So wenig sprechen, und sich doch verstehen -

Ist hohes martervolles Glück!

Always looking into each other's soul like that

And also seeing the most secret desires of the heart,

Speaking so little and yet nevertheless understanding each other

Is a high pleasure, full of martyrdom.

Gabriele von Baumberg, Der Morgenkuss (D 264)

Seine Küsse - paradiesisch Fühlen!

Wie zwei Flammen sich ergreifen, wie

Harfentöne in einander spielen

Zu der himmelvollen Harmonie -

Stürzten, flogen, schmolzen Geist in Geist zusammen,

Lippen, Wangen brannten, zitterten,

Seele rann in Seele - Erd' und Himmel schwammen

Wie zerronnen um die Liebenden!

His kisses - the feeling of Paradise! -

Like two flames engulfing each other, like

The sounds of harps playing together

To make harmony that is full of heaven,

They plunged, they flew, spirit melted into spirit,

Lips and cheeks burned, trembled -

Soul flowed into soul - Earth and heaven swam

Around the lovers as if melting away.

Schiller, Amalia (D 195)

The image of one soul flowing into another brings us back to the liquid metaphors where we began.

Related to this is a cluster of images based on the metaphor of ‘depth’.

Sie raubt der Zufall ewig nie

Aus meinem treuen Sinn,

In tiefster Seele trag' ich sie,

Da reicht kein Zufall hin.

No accident will ever tear them away

From my faithful mind:

I carry them in the depths of my soul,

Where no accident can reach them.

Seidl, Am Fenster (D 878)

Im Seelengrunde

Wohnt mir Ein Bild,

Die Todeswunde

Ward nie gestillt.

In the foundations of my soul

A single image lives on for me;

The fatal wound

Has never healed.

Schlegel, Fülle der Liebe (D 854)

Quillen doch aus allen Falten

Meiner Seele liebliche Gewalten;

Die mich umschlingen,

Himmlisch singen

For welling up out of all the recesses

Of my soul come welcome forces

Which embrace me,

They sing in a heavenly voice

Mayrhofer, Auflösung (D 807)

This takes us to another frequent set of metaphors applied to the soul in the Schubert song texts: music and harmony. Laura’s singing of Klopstock’s Resurrection Hymn makes the souls of angels even more beautiful (D 115) and another Laura’s piano playing seems to have magnetic power over a thousand souls (D 388). Harmony leads the soul to heaven (D 163) and offers sympathy to sick souls (D 302, D 394). Nightingales have a particular resonance in the human soul (Auf den Tod einer Nachtigall, D 201 D 399; Die Nachtigall, D 724). The gentle strains of a lute can drill deep down into the soul:

Sanfte Laute hör ich klingen,

Die mir in die Seele dringen,

Die mir auf des Wohllauts Schwingen

Wunderbare Tröstung bringen.

I can hear a gentle lute resound,

Which goes deep into my soul,

Which lifts me onto the wings of harmony,

Bringing me miraculous consolation.

Schober, Trost im Liede (D 546)

Here the poet’s individual soul reverberates with those of others. Most obviously, the reader’s soul hears an echo of itself and we take flight ‘on the wings of harmony’.

This reference to the ‘wings’ is an admission by the poet that the imagery of music is inadequate. This is because all metaphor falls short when it comes to these abstract concepts. Some poets portray the fusion of different souls in the language of ‘harmony’ and others (probably unconsciously) rely on water imagery (with souls flowing into each other or emotions welling up). One ambitious poet, though, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel, attempted to overcome these inherent limitations of human perception by pointing to the need to connect to the single abstract reality that animates all of these different physical images. Behind all the different words, we need to hear one single note; we need to be sensitive to this One Soul.

Es wehet kühl und leise

Die Luft durch dunkle Auen,

Und nur der Himmel lächelt

Aus tausend hellen Augen.

Es regt nur Eine Seele

Sich in des Meeres Brausen

Und in den leisen Worten,

Die durch die Blätter rauschen.

So tönt in Welle Welle,

Wo Geister heimlich trauren;

So folgen Worte Worten,

Wo Geister Leben hauchen.

Durch alle Töne tönet

Im bunten Erdentraume

Ein, nur ein leiser Ton gezogen,

Für den, der heimlich lauschet.

There is a cool and gentle movement

In the air going across the dark meadows,

And only the sky smiles

From a thousand bright eyes.

Only a single soul is stirring

In the roaring of the sea,

And in the gentle words

Which are rustling through the leaves.

Thus wave echoes wave

Where spirits are secretly grieving;

Thus words follow words,

Where spirits breathe life.

Resounding amongst all the notes

In the colourful dreams of earth,

A single faint note - just one - rings out

For the person who is secretly paying attention.

Schlegel, Die Gebüsche (D 646)

☙

Descendant of:

RELIGIONTexts with this theme:

- Verklärung, D 59 (Alexander Pope and Johann Gottfried Herder)

- An Laura, als sie Klopstocks Auferstehungslied sang, D 115 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Am See (Sitz ich im Gras), D 124 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Szene aus Faust, D 126 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Auf einen Kirchhof, D 151 (Franz von Schlechta)

- Sängers Morgenlied, D 163, D 165 (Theodor Körner)

- Sehnsucht der Liebe, D 180 (Theodor Körner)

- Die erste Liebe, D 182 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- An die Freude, D 189 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Die Mainacht, D 194 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Amalia, D 195 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Auf den Tod einer Nachtigall, D 201, D 399 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Lützows wilde Jagd, D 205 (Theodor Körner)

- Die Nonne, D 208, D 212 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Die Liebe (Freudvoll und leidvoll), D 210 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Lieb Minna, D 222 (Albert Stadler)

- Huldigung, D 240 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Alles um Liebe, D 241 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Hoffnung (Es reden und träumen die Menschen viel), D 251, D 637 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Schatzgräber, D 256 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- An den Mond (Füllest wieder Busch und Tal), D 259, D 296 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Morgenkuss, D 264 (Gabriele von Baumberg)

- Abendständchen. An Lina, D 265 (Gabriele von Baumberg)

- An Sie, D 288 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Labetrank der Liebe, D 302 (Josef Ludwig Stoll)

- Am Tage Aller Seelen / Litanei auf das Fest Aller Seelen, D 343 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- Laura am Klavier, D 388 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- An die Harmonie, D 394 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Lebens-Melodien, D 395 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Sprache der Liebe, D 410 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Entzückung, D 413 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Klage (Die Sonne steigt, die Sonne sinkt), D 415 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Blumenlied, D 431 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Das große Halleluja, D 442 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Der gute Hirt, D 449 (Johann Peter Uz)

- In der Mitternacht, D 464 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- Pflicht und Liebe, D 467 (Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter)

- Gesang der Geister über den Wassern, D 484, D 538, D 705, D 714 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Zum Punsche, D 492 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Sehnsucht (Der Lerche wolkennahe Lieder), D 516 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Am Strome, D 539 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Antigone und Oedip, D 542 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Trost im Liede, D 546 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Abschied (Lebe wohl! du lieber Freund!), D 578 (Franz Schubert)

- Elysium, D 51, D 53, D 54, D 57, D 58, D 60, D 584 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Die Geselligkeit, D 609 (Johann Carl Unger)

- An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht, D 614 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Grablied für die Mutter, D 616 (Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Die Gebüsche, D 646 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Ruhe, schönstes Glück der Erde, D 657 (Ignaz von Seyfried)

- Marie (Geistliches Lied), D 658 (Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (Novalis))

- Hymne I, D 659 (Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (Novalis))

- Kantate zum Geburtstag des Sängers Johann Michael Vogl, D 666 (Albert Stadler)

- Abendröte, D 690 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Im Walde (Waldesnacht), D 708 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Die gefangenen Sänger, D 712 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Die Nachtigall (Bescheiden verborgen), D 724 (Johann Carl Unger)

- Sei mir gegrüßt, D 741 (Friedrich Rückert)

- Am See, D 746 (Franz von Bruchmann)

- Nachtviolen, D 752 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Todesmusik, D 758 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Auf dem Wasser zu singen, D 774 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Vergissmeinnicht, D 792 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Der Müller und der Bach, D 795/19 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Der Einsame, D 800 (Karl Lappe)

- Auflösung, D 807 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die junge Nonne, D 828 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Ellens Gesang II (Jäger, ruhe von der Jagd), D 838 (Walter Scott and Philip Adam Storck)

- Totengräbers Heimwehe, D 842 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Fülle der Liebe, D 854 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Abendlied für die Entfernte, D 856 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Zwei Szenen aus dem Schauspiel “Lacrimas”, Lied der Delphine, D 857/1 (Christian Wilhelm von Schütz)

- Zwei Szenen aus dem Schauspiel “Lacrimas”, Lied des Florio, D 857/2 (Christian Wilhelm von Schütz)

- Im Jänner 1817 (Tiefes Leid), D 876 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Am Fenster, D 878 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Heimliches Lieben, D 922 (Caroline Louise Hempel)

- Am Meer, D 957/12 (Heinrich Heine)

- Die Bürgschaft, D 246 (Friedrich von Schiller)