The May night

(Poet's title: Die Mainacht)

Set by Schubert:

D 194

[May 17, 1815]

Wann der silberne Mond durch die Gesträuche blinkt,

Und sein schlummerndes Licht über den Rasen streut,

Und die Nachtigall flötet,

Wandl’ ich traurig von Busch zu Busch.

Selig preis ich dich dann, flötende Nachtigall,

Weil dein Weibchen mit dir wohnet in einem Nest,

Ihrem singenden Gatten

Tausend trauliche Küsse gibt.

Überhüllet von Laub girret ein Taubenpaar

Sein Entzücken mir vor; aber ich wende mich,

Suche dunklere Schatten,

Und die einsame Träne rinnt.

Wann, o lächelndes Bild, welches wie Morgenrot

Durch die Seele mir strahlt, find ich auf Erden dich?

Und die einsame Träne

Bebt mir heißer die Wang herab.

Whenever the silver moon gleams through the undergrowth

And strews its slumbering light over the grass,

And the nightingale sings like a flute,

I wander sadly from bush to bush.

On those occasions I consider you blessed, fluting nightingale,

Since your little wife lives with you in one nest,

To her singing spouse

She gives a thousand cosy kisses.

Covered over by foliage, a pair of doves is cooing

Their devotion in front of me; but I turn away and

Look for darker shadows,

And the single tear runs [down my cheek].

When, oh smiling image, which, like dawn

Is shining through my soul, when shall I find you on earth?

And the single tear

Feels hotter as it trembles down my cheek.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Being solitary, alone and lonely Birds Bushes and undergrowth Cheeks Covers and covering Doves and pigeons The earth Grass Heat Husband and wife Kissing Leaves and foliage Light May Morning and morning songs Nests Night and the moon Nightingales, Philomel Pictures and paintings Pouring, scattering and strewing Shade and shadows Silver Sleep Smiling Songs (general) Soul Tears and crying Walking and wandering Warbling (flöten)

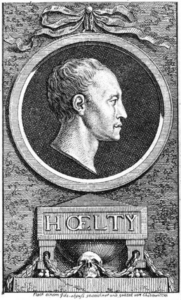

Within one month, between 17th May and 17th June 1815, Schubert set a total of thirteen poems by Hölty (D 193, D 194, D 196, D 197, D 198, D 199, D 201, D 202, D 204A, D 207, D 208, D 213, D 214). The first two of this series are both poems which begin with the effect of moonlight and they share much of the same imagery. However, the difference between the two texts is perhaps more significant: in An den Mond (D 193) the poet has lost a girl (either through death or rejection) whereas here in Die Mainacht the speaker is still on the look-out for a mate.

Consequently the central theme of the poem is the contrast between two and one. In nature the birds (nightingales and doves) have paired off, and this only serves to emphasise the speaker’s loneliness. The fact that he can only hear one nightingale singing somehow reinforces his conviction that it is loved by a partner who shares a single nest with it (note how the simple word ‘ein’ in ‘wohnet in einem Nest’ has to be translated as something stronger than ‘a’ or even ‘one’). The cooing of the doves, supposedly a declaration of love and contentment, is experienced as being performed specifically to remind the speaker of his own lack of someone to love. This is how most lonely or grieving people feel in the presence of demonstrative couples, needless to say. Hölty’s image has entered idiomatic English: they are being lovey-dovey.

The words ‘pair’ and ‘couple’ change their connotations according to what is conjoined and the state of the person contemplating them. The grieving or heart-sick persona wandering through the woods was presumably wearing a pair of shoes or boots but somehow his heart did not break as he was putting them on; it is only the awareness of mutuality and sharing (not coupledom as such) that points up a lack.

There is an even wider range of connotations and collocations for the language of being alone, not to mention all the close synonyms that hide an infinity of experience: you are on your own, she is lonely, he is lonesome, I want to be alone, they were kept in solitary confinement, a remarkable individual achievement, a solo performance, he was a hermit, she was a recluse. For the persona in this text, though, it all comes down to the fact that he is single. In turning away from happy couples a solitary tear forms and trickles down his cheek. Actually, it is so solitary that it is not ‘a’ tear, it is ‘the’ tear. On its first appearance it is referred to as ‘die einsame Träne’ (rather than ‘eine einsame Träne’, which would not only have been unmetrical but would also have taken away from the effect of the word ‘einsam’, lonesome / on its own / solitary). As this unique tear burns the speaker’s face it reveals the well of loneliness from which it flows.

One of the main differences between being solitary and being lonely relates to the extent to which we have learnt to cope with or accept the situation. In this respect the persona in Hölty’s text is not managing well, mainly because he has such a strong inner idea of what it is that he is lacking. He is determined to find that smiling image that is streaming through him like the red light of dawn; it surely cannot help that he goes on the search for this ‘Morgenrot’ (morning red / sunrise) after sunset in dark woods lit only by scattered moonlight. Nor will it help that it is now May, when spring has sprung and the rest of nature seems to have paired off successfully. Traditionally the pathetic fallacy has been seen as the deluded belief that nature shares our own emotions (that thunder storms reflect our inner turmoil, for example), but here is a clear example of nature having an effect on our inner state by its lack of feeling or sympathy.

☙

Original Spelling

Die Maynacht

Wann der silberne Mond durch die Gesträuche blinkt,

Und sein schlummerndes Licht über den Rasen streut,

Und die Nachtigall flötet,

Wandl' ich traurig von Busch zu Busch.

Selig preis' ich dich dann, flötende Nachtigall,

Weil dein Weibchen mit dir wohnet in Einem Nest,

Ihrem singenden Gatten

Tausend trauliche Küsse gibt.

Überhüllet von Laub girret ein Taubenpaar

Sein Entzücken mir vor; aber ich wende mich,

Suche dunklere Schatten,

Und die einsame Thräne rinnt.

Wann, o lächelndes Bild, welches wie Morgenroth

Durch die Seele mir strahlt, find' ich auf Erden dich?

Und die einsame Thräne

Bebt mir heisser die Wang' herab.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Gedichte von L. H. Ch. Hölty. Neu besorgt und vermehrt von Johann Heinrich Voß. Wien, 1815. Bey Chr. Kaulfuß und C. Armbruster. Gedruckt bey Anton Strauß. Meisterwerke deutscher Dichter und Prosaisten. Drittes Bändchen. page 86; with Gedichte von Ludewig Heinrich Christoph Hölty. Besorgt durch seine Freunde Friederich Leopold Grafen zu Stolberg und Johann Heinrich Voß. Hamburg, bei Carl Ernst Bohn. 1783, page 167; with Poetische Blumenlese Auf das Jahr 1775. Göttingen und Gotha bey Johann Christian Dieterich, pages 210-211; and with Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty’s Sämtliche Werke kritisch und chronologisch herausgegeben von Wilhelm Michael, Erster Band, Weimar, Gesellschaft der Bibliophilen, 1914, page 159.

To see an early version of the text, go to page 86 [164 von 300] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ15769170X