Memnon

(Poet's title: Memnon)

Set by Schubert:

D 541

[March 1817]

Den Tag hindurch nur einmahl mag ich sprechen,

Gewohnt zu schweigen immer, und zu trauern,

Wenn durch die nachtgebornen Nebelmauern

Aurorens Purpurstrahlen liebend brechen.

Für Menschenohren sind es Harmonien.

Weil ich die Klage selbst melodisch künde,

Und durch der Dichtung Glut das Rauhe ründe,

Vermuten sie in mir ein selig Blühen.

In mir, nach dem des Todes Arme langen,

In dessen tiefstem Herzen Schlangen wühlen,

Genährt von meinen schmerzlichen Gefühlen,

Fast wütend durch ein ungestillt Verlangen:

Mit dir, des Morgens Göttin, mich zu einen,

Und weit von diesem nichtigen Getriebe,

Aus Sphären edler Freiheit, reiner Liebe,

Ein stiller bleicher Stern herab zu scheinen.

In the course of the day I am only allowed to speak once,

I am used to being silent all the time, and to mourning:

When, through the walls of mist that were born during the night

Aurora’s crimson rays lovingly break.

To human ears they are harmonies.

Because I proclaim the lament so melodically myself,

And through the glow of poetry I take off the roughness,

They suppose that what is happening inside me is a happy blossoming.

Inside me – to whom death is reaching out its arms,

Within the depth of whose heart serpents are burrowing;

Nourished by my painful feelings –

Almost driven to distraction by a single, unappeased craving:

To unite myself with you, goddess of the morning,

And, far from this pointless bustle,

Out of spheres of noble freedom, pure love,

To shine down as a quiet, pale star.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Arms and embracing Breaking and shattering Clouds Ears Egypt Fire Flowers Food, feeding and nursing Harmony Hearts Heaven, the sky Here and there High, low and deep Laments, elegies and mourning Longing and yearning Melody Mist and fog Morning and morning songs Mother and child Near and far Night and the moon Noise and silence Not moving Pain Poetry Rays of light Red and purple Rough and smooth Snakes Songs (general) Spheres Stars Voices

Brooklyn Museum

Next to the city of Apollo is Thebes, now called Diospolis, “‘with her hundred gates, through each of which issue two hundred men, with horses and chariots,’” according to Homer, who mentions also its wealth; “‘not all the wealth the palaces of Egyptian Thebes contain.’” Other writers use the same language, and consider Thebes as the metropolis of Egypt. Vestiges of its magnitude still exist, which extend 80 stadia in length. There are a great number of temples, many of which Cambyses mutilated. The spot is at present occupied by villages. One part of it, in which is the city, lies in Arabia; another is in the country on the other side of the river, where is the Memnonium. Here are two colossal figures near one another, each consisting of a single stone. One is entire; the upper parts of the other, from the chair, are fallen down, the effect, it is said, of an earthquake. It is believed, that once a day a noise as of a slight blow issues from the part of the statue which remains in the seat and on its base. When I was at those places with Ælius Gallus, and numerous friends and soldiers about him, I heard a noise at the first hour (of the day), but whether proceeding from the base or from the colossus, or produced on purpose by some of those standing around the base, I cannot confidently assert. For from the uncertainty of the cause, I am disposed to believe anything rather than that stones disposed in that manner could send forth sound. Strabo, Geography XVII: 1, 46 Early 1st Century AD English translation by H.C. Hamilton and W. Falconer

In Egyptian Thebes, on crossing the Nile to the so called Pipes, I saw a statue, still sitting, which gave out a sound. The many call it Memnon, who they say from Aethiopia overran Egypt and as far as Susa. The Thebans, however, say that it is a statue, not of Memnon, but of a native named Phamenoph, and I have heard some say that it is Sesostris. This statue was broken in two by Cambyses, and at the present day from head to middle it is thrown down; but the rest is seated, and every day at the rising of the sun it makes a noise, and the sound one could best liken to that of a harp or lyre when a string has been broken. Pausanius, Description of Greece 2nd Century AD English translation by W.H.S. Jones

I wish to describe to you the miracle of Memnon also; for the art it displayed was truly incredible and beyond the power of human hand. There was in Ethiopia an image of Memnon, the son of Tithonus, made of marble; however stone though it was, it did not abide within its proper limits nor endure the silence imposed on it by nature, but stone though it was it had the power of speech. For at one time it saluted the rising Day, by its voice giving token of its joy and expressing delight at the arrival of its mother; and again, as day declined to night, it uttered piteous and mournful groans in grief at her departure. Nor yet was the marble at a loss for tears, but they too were at hand to serve its will. The statue of Memnon, as it seems to me, differed from a human being only in its body, but it was directed and guided by a kind of soul and by a will like that of man. At any rate it both had grief in its composition and again it was possessed by a feeling of pleasure according as it was affected by each emotion. Though nature had made all stones from the beginning voiceless and mute and both unwilling to be under the control of grief and also unaware of the meaning of joy, but rather immune to all the darts of chance, yet to that stone of Memnon art had imparted pleasure and had mingled the sense of pain in the rock; and this is the only work of art of which we know that has implanted in the stone perceptions and a voice. Callistratus, Descriptions 9 (On the statue of Memnon) 3rd Century AD English translation by Arthur Fairbanks

These extracts from ancient guidebooks refer to a time between 27 BC and 199 AD when tourists flocked to Egyptian Thebes / Luxor to hear a colossal statue greet the dawn. The modern consensus is that the sound was originally caused by damage to the ancient statue in the earthquake of 27 BC and can be explained on the basis of regular daily changes in temperature and atmospheric conditions. The fact that the singing stopped after the Emperor Septimius Severus ordered the figure to be repaired in 199 AD seems to support this theory.

Mayrhofer’s poem, eavesdropping on the three thousand year old statue’s inner thoughts, was written at the very beginning of scientific Egyptology, between Napoleon’s ‘Commission des sciences et des arts’, which accompanied him to Egypt in 1798, and Champollion’s decoding of the hierogylphs on the Rosetta Stone in 1822. Mayrhofer is less interested in the bald facts about the statue of Memnon than in the way that different audiences have (mis)understood it. However, before we can read the text from that viewpoint it would be helpful to clarify what is now known about the figure itself.

captioned “Thèbes, Memnonium: Vue des deux colosses”

‘Memnon’ is the northern one of two colossal (18 meter high) statues built on the west bank of the Nile at the entrance to Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. They would both have been originally intended to represent the Pharaoh himself (Amenhotep III, 1386 – 1349 BCE). Although the reign of Amenhotep III was enormously successful in uniting Egypt and projecting its power, his memory soon began to fade. His son, Akhenaten, turned against the cult of Amun (referred to in the name Amen-hotep) and moved the capital away from Thebes. Because Amenhotep III’s funerary temple was built too close to the Nile floodplain, it had fallen into ruin within two centuries and its stones were recycled in later buildings in Karnak / Luxor. Thus it was that the two colossal statues were left, with little memory of who they represented.

Homer, and Greek story-tellers in the generations before and after him, reported that at a critical point in the Trojan War Achilles killed Memnon, a king from Ethiopia who had led a force to defend Troy. This Memnon was the son of Tithonos (a relative of King Priam of Troy) and Eos (later known as Aurora, the goddess of dawn). It is not known when the Colossus at Thebes first came to be thought of as a statue of this Memnon, but there had been significant interaction between Greek and Egyptian culture even before Alexander the Great incorporated the Nile (valley and delta) into his greater empire. Under his successors, the Ptolemies, Greek language and culture were integral to Egyptian life, so it is hardly surprising that an imposing statue looking towards the East came to be interpreted as Memnon, the son of Eos / Aurora / Dawn. At a time when Alexandria had taken over as the capital of Egypt, Thebes appeared to be remote, more ‘African’, and so it made sense to see the Colossus as ‘Ethiopian’.

The Roman era corresponded with the phenomenon of the ‘singing statue’. Memnon was therefore at this time remembered more as the son of Aurora, the Dawn, since his song was interpreted as him calling out to greet his mother. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses 13:576 (written between c.1 and 8 AD) there is a vivid description of the impact of the Trojan War on the bereaved widows and mothers. After reporting the story of Hecuba being reduced to a howling fury, the author tells of Aurora’s grief over the death of Memnon at the hands of Achilles and how, from his funeral pyre, a flock of aggressive birds emerged (the Memnonides). This was taken as a sign that Jupiter had accepted Aurora’s plea for her loss of Memnon never to be forgotten.

Although Aurora had given aid to Troy, she had no heart nor leisure to be moved by fall of Troy or fate of Hecuba. At home she bore a greater grief and care; her loss of Memnon is afflicting her. Aurora, his rose-tinted mother, saw him perish by Achilles' deadly spear, upon the Phrygian plain. She saw his death, and the loved rose that lights the dawning hour turned death-pale, and the sky was veiled in clouds. Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.576 English translation by Brookes More, 1922

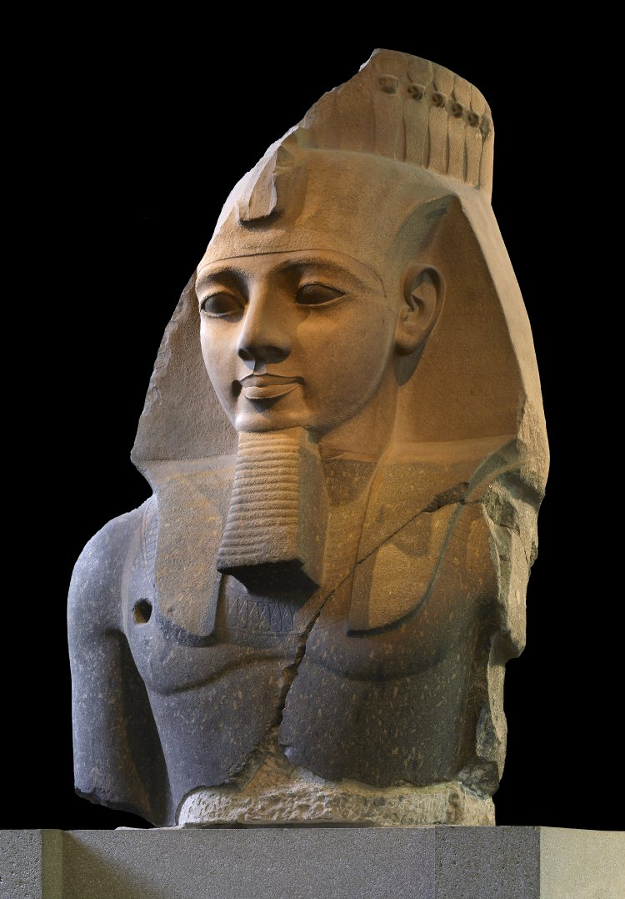

Louvre Museum

Nor was Memnon fully forgotten during the long years between the silencing of the statue and revived European interest in the ruins of Egypt in the 18th century (encouraged as much by the rise of Freemasonry as the beginnings of ‘scientific’ Egyptology). Since educated Europeans were likely to approach Egypt through their familiarity with Latin and Greek sources, it is not surprising that they continued to read Egyptian remains through the lens of Homer and Ovid. When Napoleon’s Egyptologists began to study the remains on the West bank of the Nile at Thebes next to the famous pair of Colossi they concluded that they had found the ‘Memnonium’, the funerary complex of Memnon himself. In 1815 the British Consul General arranged to have a massive fallen head dug up from this area to be sent to London. The English (relishing their recent defeat of the French and their sense that they were living through significant historical events) were keen to welcome ‘The Younger Memnon’.

London, British Museum

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=117633&partId=1

It did not take long for some classicists to suggest that what had been found was not the funeral complex of Memnon, but that of a mighty Egyptian ruler Osymandyas, whose massive buildings at Thebes had been described by Diodorus of Sicily (1st Century BCE) in Book 1 of his ‘Bibliotheca historica’. Could the head and shoulders making their slow way from Thebes to London be the very work he evoked so vividly?

And it is not merely for its size that this work merits approbation, but it is also marvellous by reason of its artistic quality and excellent because of the nature of the stone, since in a block of so great a size there is not a single crack or blemish to be seen. The inscription upon it runs: "King of Kings am I, Osymandyas. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works." (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 1.47.4 English translation by C. H. Oldfather)

It was not long after the figure arrived in the British Museum in 1821 that the mystery was resolved. The deciphering of hieroglyphics made it possible to conclude that the Greek name Osymandyas (Ὀσυμανδύας) must have been derived from part of the throne name of Ramesses II: Usermaatre Setepenre. The Memnonium was in fact the Ramesseum. It therefore also became clear that the Colossi of Memnon had been connected with an earlier complex on the same site in honour of Amenhotep III. ‘Memnon’ was in fact Pharaoh Amenhotep III and ‘Younger Memnon’ was a younger Pharaoh, Ramesses II.

London, British Museum

Even as the 7.25 ton stone that was still known as the Younger Memnon was on its way to northern Europe, three poets were working on texts that would attempt to interpret the significance of such figures in the modern age. It is not known when Mayrhofer wrote his ‘Memnon’ but it cannot have been long before Schubert set it to music in March 1817. At the end of the same year (December 1817) the stockbroker and novelist Horace Smith visited Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary (who was currently putting the finishing touches to ‘Frankenstein’). Smith and Shelley challenged each other to a sonnet-writing competition on the subject of ‘Osymandias’ (perhaps inspired by the imminent arrival in London of the Younger Memnon). The resulting two sonnets were published in early 1818:

In Egypt's sandy silence, all alone, Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws The only shadow that the Desert knows:— "I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone, "The King of Kings; this mighty City shows "The wonders of my hand."— The City's gone,— Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose The site of this forgotten Babylon. We wonder,—and some Hunter may express Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace, He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess What powerful but unrecorded race Once dwelt in that annihilated place. Horace Smith (1779 - 1849)

I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert... near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal these words appear: 'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings; Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!' Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 - 1822)

For the two English poets the statue speaks of the transience of power. Neither writer is in any doubt about the moral that is being pointed: all Empires and Tyrants will eventually crumble. Just as England and London were emerging as the greatest power and most influential city on earth, the inhabitants were being invited to envisage a time when it would all be ‘silent’, ‘desert’, ‘wilderness’, ‘decay’, ‘bare’, ‘annihilated’.

We can use this shared vision to highlight how differently Mayrhofer approached the same topic at the same time from his perspective in Vienna. For him, the colossal statue is still intact and it is far from transient. His Memnon suffers not from decay but from being trapped forever in the same position. Where Oyzmandias was said to proclaim a simple statement of power (albeit one which has become ironic in the light of later events) – ‘this mighty City shows The wonders of my hand’ / ‘Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair’ – Mayrhofer’s Memnon finds that his own utterances (limited as they are) are always misunderstood. The crowds who come to marvel at his greeting of the dawn do not have the first idea about what it is that he is expressing.

Mayrhofer is himself so trapped in his situation that he cannot envisage an age when the authoritarian Austrian regime which dominated his life would be reduced to rubble. He is himself so isolated that he feels that all of his utterances are misunderstood. HE is the statue of Memnon, fixed and frustrated, longing for an impossible freedom.

‘Für Menschenohren sind es Harmonien’ / ‘To human ears they are harmonies’. Mayrhofer imagines the pain of an imprisoned figure who can see crowds of tourists enjoying his daily song but he can say nothing else. Memnon has to sit in silence as generation after generation misunderstands and misrepresents his only utterance. They are convinced that his song is an expression of the character’s blossoming, that he is delightedly greeting each new day. They cannot know, or even imagine, that it is a cry of agony as day after day he is reminded of his inability to escape ‘weit von diesem nichtigen Getriebe’ / ‘far from this pointless bustle’. There is simply no way of pointing out their misapprehension to them.

So for Mayrhofer, Memnon speaks for those of us who are painfully aware of the disjunction between what we would like to express, our inner intention, and what our audience actually understands by what we say or write. Although Wittgenstein tried to argue that this is a false dichotomy, that there is in fact no ‘inner message’ that fails to get captured in what we actually say, most of us continue to believe that we frequently fail to say what we mean, that we have not managed to find the appropriate words to express the complex reality that remains trapped within. This is all part of the idea of an inner self that is unknowable to others.

Mayrhofer’s Memnon is thus no ruler or soldier, he is a prisoner longing for escape, an exile longing for his homeland, a son longing for his mother. He is a poet. His constraints are those of the poet in any restrictive environment; he is left with no choice but to limit his utterances to the narrow confines that are permitted. Yet these very restrictions serve to intensify the power of what CAN be expressed. We are dealing with the mystery of poetry itself, the astonishing fact that formulaic structures and the constraints of metre, rhyme, assonance etc. result in novel, unexpected ideas and perceptions. The colossal statue of Memnon embodies the forbidding structures of poetic form, and Mayrhofer’s poem allows us to hear an eloquent voice that is already ‘far from this pointless bustle’ (weit von diesem nichtigen Getriebe) where we spend most of our time.

We could perhaps compare Mayrhofer in Metternich’s Vienna with artists in other oppressive systems who have managed to assert their freedom in spite of everything. Shostakovich, for example, managed to write symphonies that sounded either hopeful or bombastic and critical depending on the attitude of the listener. Like Memnon, he produced sounds that were ‘harmonious’ to the uncritical masses (or to the regime) but which were a cry of outrage to those with ears to hear. Like Memnon, his ability to express a yearning to belong to ‘spheres of noble freedom, pure love’ is what allows us to escape our own constraints.

Memnon did not just have a voice between 27BC and 199AD. Through an obscure poem written by Mayrhofer and set to music by his friend and later flatmate Schubert in March 1817, the stone continues to sing.

By Tim Dellmann – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5166873

☙

Original Spelling Memnon Den Tag hindurch nur einmahl mag ich sprechen, Gewohnt zu schweigen immer, und zu trauern: Wenn durch die nachtgebornen Nebelmauern Aurorens Purpurstrahlen liebend brechen. Für Menschenohren sind es Harmonien. Weil ich die Klage selbst melodisch künde, Und durch der Dichtung Gluth das Rauhe ründe, Vermuthen sie in mir ein selig Blühen. In mir - nach dem des Todes Arme langen, In dessen tiefstem Herzen Schlangen wühlen; Genährt von meinen schmerzlichen Gefühlen - Fast wüthend durch ein ungestillt Verlangen: Mit dir, des Morgens Göttin, mich zu einen, Und weit von diesem nichtigen Getriebe, Aus Sphären edler Freyheit, reiner Liebe, Ein stiller bleicher Stern herab zu scheinen.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 160.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 160 [174 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902