May song

(Poet's title: Mailied)

Set by Schubert:

D 129

for TTB trio[1815?]

D 199

[May 24, 1815]

D 503

[November 1816]

Part of The Theresa Grob Album

Grüner wird die Au

Und der Himmel blau,

Schwalben kehren wieder,

Und die Erstlingslieder

Kleiner Vögelein

Zwitschern durch den Hain.

Aus dem Blütenstrauch

Weht der Liebe Hauch:

Seit der Lenz erschienen,

Waltet sie im Grünen,

Malt die Blumen bunt,

Roth des Mädchens Mund.

Brüder, küsset ihn!

Denn die Jahre fliehn!

Einen Kuss in Ehren

Kann euch niemand wehren.

Küsst ihn, Brüder, küsst,

Weil er küsslich ist.

Seht, der Tauber girrt,

Seht, der Tauber schwirrt

Um sein liebes Täubchen.

Nehmt euch auch ein Weibchen,

Wie der Tauber tut,

Und seid wohlgemut.

The meadow is becoming greener,

And the sky blue;

Swallows are returning

And the first songs

Of small birds

Are chirrupping through the grove.

Out of wreaths of blossom

The breath of love is wafting.

Since spring appeared

It has been at work out in the open

Painting the flowers bright colours

And the girl’s mouth red.

Brothers, kiss it!

For the years are flying past!

One kiss in veneration –

Nobody could object to that!

Kiss it, brothers, kiss,

Because it is kissable!

Look, the male dove is cooing,

Look, the male dove is flitting

Around his beloved little dove!

You too, take a little wife

Just as the male dove is doing

And be cheerful!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Birds Blue Breath and breathing Brothers and sisters Doves and pigeons Fields and meadows Flowers Flying, soaring and gliding Green Heaven, the sky Joy Kissing May Mouths Pictures and paintings Red and purple Songs (general) Spring (season) Swallows Woods – groves and clumps of trees (Hain) Wreaths and garlands

If it is all so natural, why is any persuasion needed? The first two stanzas of this seemingly simple lyric appear to be a neutral description of the arrival of Spring and the changing colours of nature, but the second half of the text becomes an explicit appeal to take lessons from the birds and the bees. Fellow males (‘brothers’) should ignore possible objections and take the initiative in terms of bonding and mating behaviour.

The language conflates two discourses to hide the rhetorical trick being performed. On one level, diminutives are used to express affection and so-called innocence. The -chen suffix in German makes the noun longer and its referent smaller, so ‘ein Täubchen’ is a diminutive ‘Taube’ (dove or pigeon); ein Mädchen (a girl) is a little Magd (maid). It also makes a female noun neuter (so words like Mädchen, girl, are referred to using ‘it’ rather than ‘she’). However, ‘ein Weibchen’ (in the final instruction, Nehmt euch ein Weibchen) is not just a diminutive and seemingly affectionate ‘little wife’. Despite her neuter gender in the grammatical system, she is explicitly female, and a sexualised female at that, since this is the word used in ornithology (and zoology generally) to denote ‘the female of the species’ (the corresponding male is a Männchen, a little man). The brothers are therefore being urged both to get themselves ‘a little woman’ and to get hold of ‘a female’.

Why should we behave like doves? Even if we should, who is to say which doves we should take as our models? Some of them have courting behaviour where the male is more colourful and the female takes the initiative in making the selection of a partner, but these examples do not fit the aggressive heterosexuality assumed and asserted by the persona of Hölty’s poem.

The poet has also used a rhetorical trick to persuade us that human sexuality is part of a natural rather than a cultural rhythm. Spring might be said to make the grass greener and the fields more colourful in general, but it is not the main thing that is responsible for the redness of girls’ mouths. Having a cold might be just as effective, but that would not fit the patriarchal agenda. The brothers are enjoined to kiss the girl’s mouth since it is ‘kissable’. It may be that the word ‘küßlich’ (kissable) echoes the similar sounding ‘köstlich’ (valuable), but it hardly constitutes a strong argument (‘the mouth is kissable so you should kiss it’).

In this text mouths are receptive and waiting to be kissed. It is interesting to contrast Hölty’s lyric with Schikaneder’s use of exactly the same imagery in The Magic Flute (1791), where Papageno, the bird catcher, refuses to trap his own female; he dreams not of catching and kissing but of being caught and being kissed:

Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,

Wünscht Papageno sich!

O so ein sanftes Täubchen

Wär’ Seligkeit für mich.

Wird keine mir Liebe gewähren,

So muß mich die Flamme verzehren!

Doch küßt mich ein weiblicher Mund,

So bin ich schon wieder gesund.

A girl or a little wife

Is what Papageno wants for himself!

O such a gentle little dove

Would be bliss for me.

If noone will grant me love,

The flames will have to consume me!

But if a female mouth were to kiss me,

I would soon be better again.

In Schikaneder’s song the mouth kisses a person (‘me’), where in Hölty the brothers are encouraged to kiss the girl’s mouth. Not ‘kiss the girl’ or even ‘kiss the girl on the mouth’, just ‘kiss the mouth’. Kiss ‘it’, the mouth. Brothers plural; mouth singular. It, like the unnamed girl herself, has been objectified. Surely, as Hölty (or his persona) comments in stanza 3, nobody can object! The very fact that he felt he had to make this comment, though, suggests that there might be people who found, and continue to find, the attitude objectionable.

☙

Original Spelling Maylied Grüner wird die Au, Und der Himmel blau; Schwalben kehren wieder, Und die Erstlingslieder Kleiner Vögelein Zwitschern durch den Hain. Aus dem Blütenstrauch Weht der Liebe Hauch: Seit der Lenz erschienen, Waltet sie im Grünen, Malt die Blumen bunt, Roth des Mädchens Mund. Brüder, küsset ihn! Denn die Jahre fliehn! Einen Kuß in Ehren Kann euch Niemand wehren! Küßt ihn, Brüder, küßt, Weil er küßlich ist! Seht, der Tauber girrt, Seht, der Tauber schwirrt Um sein liebes Täubchen! Nehmt euch auch ein Weibchen, Wie der Tauber thut, Und seid wohlgemut!

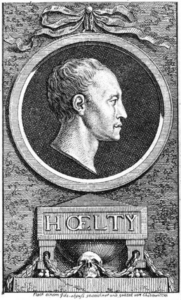

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Gedichte von L. H. Ch. Hölty. Neu besorgt und vermehrt von Johann Heinrich Voß. Wien, 1815. Bey Chr. Kaulfuß und C. Armbruster. Gedruckt bey Anton Strauß. Meisterwerke deutscher Dichter und Prosaisten. Drittes Bändchen. pages 129-130; with Gedichte von Ludewig Heinrich Christoph Hölty. Besorgt durch seine Freunde Friederich Leopold Grafen zu Stolberg und Johann Heinrich Voß. Carlsruhe, bey Christian Gottlieb Schmieder, 1784, pages 22-23, and with Poetische Blumenlese für das Jahr 1779. Herausgegeben von Joh. Heinr. Voß. Hamburg, bei Carl Ernst Bohn, pages 7-8.

This is Hölty’s poem in its first version, posthumously printed in the first edition (edited by Voß). Hölty’s poem exists in 6 manuscript copies, later versions differ significantly.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 129 [207 von 300] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ15769170X