☙

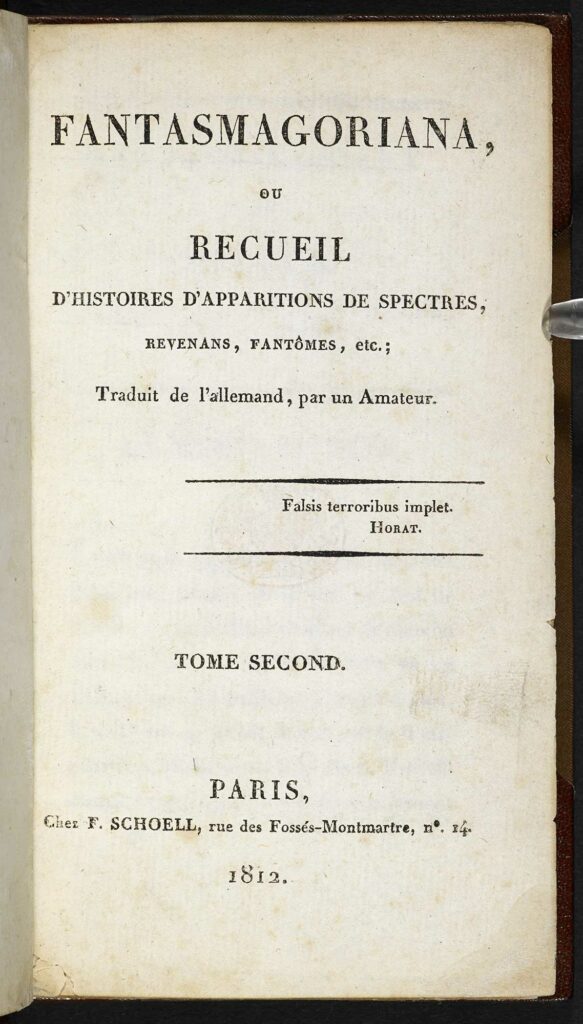

The relentless rain of June 1816 kept the tenants of the Villa Diodati indoors. Byron, Polidori, Shelley, Mary Godwin (later Shelley) and Claire Clairmont spent their time reading the recently published ‘Fantasmagoriana’, a French translation of German ghost stories compiled by Apel and Laun (and published in 5 volumes between 1810 and 1815). Their reading then inspired them to tell and write their own horror stories, including Polidori’s ‘The Vampyre’ and Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’.

It has become a commonplace of English literary history that this moment represents the birth of the gothic horror genre, even though there is plenty of evidence that similar ghost stories had already been popular for over two generations. Schubert as a young man was clearly attracted to a variety of such tales, from vengeful nuns haunting village chapels (Die Nonne, D 208, D 212) to Ossianic spirits hovering over remote bogs and heaths (Lodas Gespenst, D 150). It is also a mistake to read this attraction to the ‘gothic’ as a reaction to or rejection of the ‘classical’ tradition. The Greeks wrote about and believed in various types of ‘spirit’, and Schubert’s close friend Mayrhofer often evokes the sounds of spirits or ghosts in his ‘classical’ writing (e.g. the voices of the spirits that can be heard in ‘Fahrt zum Hades’, D 526; the frightening ‘ghostly sounds’ in ‘Der Schiffer’, D 536; the trees that rustle like ghosts in ‘Auf der Donau’, D 553).

Needless to say, there is a similar fusion of ‘romantic’ and ‘classical’ elements in the texts of Goethe that Schubert set to music. An old Germanic hero issues a greeting to future travellers (all figures of the ‘Enlightenment’) who pass by his old castle in ‘Geistes-Gruß’, D 142. A reflection on the physical phenomena surrounding a waterfall (gravity, movement, reflections, time etc) involves both a scientific and a theological approach to the nature of ‘spirits’ in ‘Gesang der Geister über den Wassern’, D 484, D 538, D 705 and D 714.

Spirits can range from Shinto-like spirits of the place (as in the old man of the mountain who appears as a spirit to the young hunter in Schiller’s ‘Der Alpenjäger’, D 588) to the spirits or souls of the recently deceased whose presence is intuited by those they have left behind (‘Abends unter der Linde’, D 235, D 237, and ‘Schwestergruß’, D 762). In a couple of the texts the word ‘Geist’ is clearly used to mean spirit as opposed to flesh, as in the Gospel of John (“It is the spirit that quickeneth; the flesh profiteth nothing: the words that I speak unto you, they are spirit, and they are life.” John 6:63). In Mayrhofer’s dualistic ‘An die Freunde’ D 654 the power of loving friends rises into the realm of the spirit, whereas the rotting corpse of the speaker sinks further into the physical earth. For poets of sensibility (such as Matthisson, e.g. ‘Naturgenuss’ D 188, D 442), the spirit that infuses all of nature allows us to escape this physical realm. Later romantic poets, such as Friedrich von Schlegel, link this idea of spirit within nature to the spirit that reveals itself to us in the experiences of love and of art. The lover and the poet open themselves up to this pervasive spiritual reality and are thereby released from more physical concerns:

Ein Zauber waltet Jetzt über mich, Und der gestaltet Dies all' nach sich. Als ob uns vermähle Geistesgewalt, Wo Seel' in Seele Hinüberwallt. There is a magic Over me now, And which is forming All of this in its own way, As if we were being wedded By the power of a spirit, Where soul joins soul As they surge onwards. Schlegel, Fülle der Liebe D 176 Wo Geister heimlich trauren; So folgen Worte Worten, Wo Geister Leben hauchen. Durch alle Töne tönet Im bunten Erdentraume Ein, nur ein leiser Ton gezogen, Für den, der heimlich lauschet. Where spirits are secretly grieving; Thus words follow words, Where spirits breathe life. Resounding amongst all the notes In the colourful dreams of earth, A single faint note - just one - rings out For the person who is secretly paying attention. Schlegel, Die Gebüsche D 646

☙

Descendant of:

THE COURSE OF HUMAN LIFE: From the cradle to the grave RELIGION REALITY AND UNREALITYTexts with this theme:

- Thekla (eine Geisterstimme), D 73, D 595 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Geistes-Gruß, D 142 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Die Sterne (Was funkelt ihr so mild mich an), D 176 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- Die erste Liebe, D 182 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- Lodas Gespenst, D 150 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Naturgenuss, D 188, D 422 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Die Nonne, D 208, D 212 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Die Laube, D 214 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Abends unter der Linde, D 235, D 237 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Cronnan, D 282 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Minona oder die Kunde der Dogge, D 152 (Friedrich Anton Franz Bertrand)

- Am Tage Aller Seelen / Litanei auf das Fest Aller Seelen, D 343 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- Gesang der Geister über den Wassern, D 484, D 538, D 705, D 714 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Wanderer (Ich komme vom Gebirge her), D 489 (Georg Philipp Schmidt)

- Fahrt zum Hades, D 526 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die Nacht, D 534 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Der Schiffer, D 536 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Auf der Donau, D 553 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Der Alpenjäger, D 588 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Die Gebüsche, D 646 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- An die Freunde, D 654 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Schwestergruß, D 762 (Franz von Bruchmann)

- Geisterchor, D 797/4 (Wilhelmine Christiane von Chézy)

- Des Sängers Habe, D 832 (Franz von Schlechta)

- Fülle der Liebe, D 854 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)