Song (Who is Silvia?)

(Poet's title: Gesang)

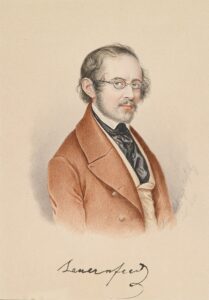

Set by Schubert:

D 891

[July 1826]

Was ist Silvia, saget an,

Dass sie die weite Flur preist?

Schön und zart seh ich sie nahn,

Auf Himmels Gunst und Spur weist,

Dass ihr Alles untertan.

Ist sie schön und gut dazu?

Reiz labt wie milde Kindheit,

Ihrem Aug eilt Amor zu,

Dort heilt er seine Blindheit

Und verweilt in süßer Ruh.

Darum Silvia tön, o Sang,

Der holden Silvia Ehren,

Jeden Reiz besiegt sie lang,

Den Erde kann gewähren,

Kränze ihr und Saitenklang.

What is it about Silvia, tell us,

That leads the meadows all around to praise her?

I can see her approach, beautiful and tender,

The benevolence and trace of heaven signify

That everything should be subject to her.

Along with that, is she beautiful and good?

Charm soothes like gentle childhood;

Cupid hurries towards her eyes,

He cures his blindness there,

And dwells in sweet rest.

Therefore let singing ring out for Silvia,

In honour of beauteous Silvia;

She has long conquered every charm

That earth can grant:

Let her have garlands and the playing of strings!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Amor / Cupid Children and childhood Eyes Fields and meadows Heaven, the sky Rest Soothing and healing Stringed instruments (unspecified) Wreaths and garlands

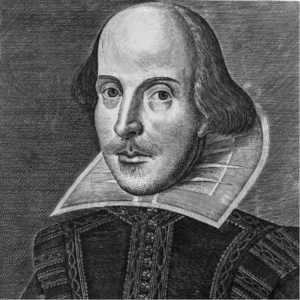

Who is Silvia? In the context of The Two Gentlemen of Verona (written c. 1590), she is the daughter of the Duke of Milan. Although her father has promised her hand in marriage to Turio, she is in love with Valentine (and he with her). Valentine’s friend Proteus (the second ‘gentleman of Verona’) also falls in love with her (thereby breaking his promise to his girlfriend Julia, back in Verona). This song (the only one in the course of the play) is sung outside her window as part of a plot by Proteus whereby he claimed he was helping Turio win her affection while doing everything possible to win her for himself.

The scene in which Proteus persuades Turio to use poetry and music to win Silvia round prepares the audience for the performance of the serenade:

PROTEUS Say that upon the altar of her beauty You sacrifice your tears, your sighs, your heart. Write till your ink be dry, and with your tears Moist it again, and frame some feeling line That may discover such integrity; For Orpheus' lute was strung with poets' sinews, Whose golden touch could soften steel and stones, Make tigers tame and huge leviathans Foresake unsounded deeps to dance on sands. Visit by night your lady's chamber-window With some sweet consort; to their instruments Tune a deploring dump. The night's dead silence Will well become such sweet-complaining grievance. This, or else nothing, will inherit her. William Shakespeare, The Two Gentlemen of Verona Act III Scene 2 lines 72 - 86 Edited by William C. Carroll (The Arden Shakespeare), 2004

Proteus then arranges for musicians to perform, but he is unaware that Julia has followed him to Milan disguised as a boy.

Enter PROTEUS PROTEUS Already have I been false to Valentine, And now I must be as unjust to Turio. Under the colour of commending him I have access my own love to prefer. But Silvia is too fair, too true, too holy To be corrupted with my worthless gifts. When I protest true loyalty to her, She twits me with my falsehood to my friend; When to her beauty I commend my vows, She bids me think how I have been foresworn In breaking faith with Julia, whom I loved. And notwithstanding all her sudden quips, The least whereof would quell a lover's hope, Yet, spaniel-like, the more she spurns my love, The more it grows and fawneth on her still. [Enter TURIO and Musicians] But here comes Turio. Now must we to her window, And give some evening music to her ear. TURIO How now, Sir Proteus, are you crept before us? PROTEUS Ay, gentle Turio, for you know that love Will creep in service where it cannot go. TURIO Ay, but I hope, sir, that you love not here. PROTEUS Sir, but I do, or else I would be hence. TURIO Who? Silvia? PROTEUS Aye, Silvia - for your sake. TURIO I thank you for your own. Now, gentlemen, Let's tune, and to it lustily awhile. [Enter Host and JULIA in boy's clothes, as Sebastian.] HOST Now my young guest, methinks you're allicholy. I pray you, why is it? JULIA Marry, mine host, because I cannot be merry. HOST Come, we'll have you merry. I'll bring you where you shall hear music, and see the gentleman that you asked for. JULIA But shall I hear him speak? HOST Aye, that you shall. JULIA That will be music. [Music plays] HOST Hark! Hark! JULIA Is he among these? HOST Aye, but peace, let's hear 'em. SONG Who is Silvia? What is she, That all our swains commend her? Holy, fair and wise is she; The heaven such grace did lend her, That she might admired be. Is she kind as she is faire? For beauty lives with kindness. Love doth to her eyes repair To help him of his blindness, And, being helped, inhabits there. Then to Silvia let us sing, That Silvia is excelling; She excels each mortal thing Upon the dull earth dwelling. To her let us garlands bring. HOST How now, are you sadder than you were before? How do you, man? The music likes you not. JULIA You mistake, the musician likes me not. HOST Why, my pretty youth? JULIA He plays false, father. HOST How, out of tune on the strings? JULIA Not so, but yet so false that he grieves my very heart-strings. HOST You have a quick ear. JULIA Ay, I would I were deaf; it makes me have a slow heart. HOST I perceive you delight not in music. JULIA Not a whit, when it jars so. HOST Hark, what fine change is in the music! JULIA Ay, that change is the spite. HOST You would have them always play but one thing? JULIA I would always have one play but one thing. William Shakespeare, The Two Gentlemen of Verona Act IV Scene 2 lines 1 - 69 Edited by William C. Carroll (The Arden Shakespeare), 2004

Note that no stage direction indicates who performs the song, though Julia’s response suggests that it was probably Proteus. She is aware that he ‘plays false’ (i.e. he has betrayed her). Her presence on stage during the serenade reminds the audience that the text is not a sincere expression of passion for Silvia. Proteus constructed it (and perhaps performed it) as an act of betrayal against his former friend Valentine, as a means of manipulating Turio and fully aware that he was abandoning Julia. Shakespeare’s first audience was therefore being invited to see this love song as a clever exercise in rhetoric more than an expression of genuine emotion.

Part of the trick is that the daughter of a Duke (he is even referred to as ‘Emperor’ in earlier scenes) in a major urban centre like Milan is hailed using the conventions of the Pastoral tradition. Her name, Silvia, evokes the sylvan (woodland) settings of Latin writers like Virgil, and she is said to be adored (‘commended’) by ‘swains’ (agricultural labourers). There is another classical allusion in the second stanza:

Love doth to her eyes repair To help him of his blindness

This is a reference to Amor or Cupid and the conventional wisdom that ‘love is blind’. Yet the use of the simple English word ‘Love’ in place of the Latin ‘Amor’ works as a double-bluff. Only someone truly versed in the conventions of Renaissance rhetoric would have been expected to pick up the reference.

In the context of the play, the relationship between love and blindness is a recurring theme. The most significant exchange in relation to this comes in Act II just before Proteus arrives in Milan. Valentine and Turio (Silvia’s two suitors) are with her when they hear the news of his arrival:

VALENTINE This is the gentleman I told your ladyship Had come along with me, but that his mistress Did hold his eyes locked in her crystal looks. SILVIA Belike that now she hath enfranchised them Upon some other pawn for fealty. VALENTINE Nay, sure, I think she holds them prisoners still. SILVIA Nay, then he should be blind, and being blind How could he see his way to seek out you? VALENTINE Why, lady, Love hath twenty pair of eyes. TURIO They say that Love hath not an eye at all. VALENTINE To see such lovers, Turio, as yourself; Upon a homely object, Love can wink. William Shakespeare, The Two Gentlemen of Verona Act II Scene 4 lines 85 - 96 Edited by William C. Carroll (The Arden Shakespeare), 2004

Love doth to her eyes repair To help him of his blindness, And, being helped, inhabits there.

The claim is not just that she helps cure Love of his blindness, but that Love has now taken up residence in Silvia’s own eyes. Whoever she looks at receives Cupid’s arrow (it was generally believed that eyes emitted rather than received light, so it was her glance that made people fall in love with her).

| Shakespeare (First Folio, 1623) | Bauernfeld | Back translation from Bauernfeld |

| Who is Silvia? what is she? That all our Swaines commend her? Holy, faire, and wise is she. The heavens such grace did lend her, That she might admired be. Is she kinde as she is faire? For beauty lives with kindnesse: Love doth to her eyes repaire, To helpe him of his blindnesse: And being help’d, inhabits there. Then to Silvia, let us sing, That Silvia is excelling; She excels each mortall thing Upon the dull earth dwelling. To her let us Garlands bring. | Was ist Silvia, saget an, Daß sie die weite Flur preist? Schön und zart seh’ ich sie nah’n, Auf Himmels Gunst und Spur weist, Daß ihr Alles unterthan. Ist sie schön und gut dazu? Reiz labt wie milde Kindheit; Ihrem Aug’ eilt Amor zu, Dort heilt er seine Blindheit, Und verweilt in süßer Ruh. Darum Silvia tön’, o Sang, Der holden Silvia Ehren; Jeden Reiz besiegt sie lang, Den Erde kann gewähren: Kränze ihr und Saitenklang! | What is it about Silvia, tell us, That leads the meadows all around to praise her? I can see her approach, beautiful and tender, The benevolence and trace of heaven indicate That everything should be subject to her. Along with that, is she beautiful and good? Charm soothes like gentle childhood; Cupid hurries towards her eyes, He cures his blindness there, And dwells in sweet rest. Therefore let singing ring out for Silvia, In honour of beauteous Silvia; She has long conquered every charm That earth can grant: Let her have garlands and the playing of strings! |

Bauernfeld’s German translation is remarkably close to the English original. It keeps the same rhyme scheme and metre (which means that Schubert’s music can actually be sung to Shakespeare’s words, even though the composer would never have seen or understood those). However, Bauernfeld made no attempt to translate ‘swains’ (all our swains commend her). He says that it is the whole ‘meadow’ that praises Silvia, perhaps associating her name with the plant salvia. Although there could be no exact translation of ‘Silvia is excelling’ (stanza 3), Bauernfeld expresses the same idea at the end of the first verse: ‘Daß ihr Alles unterthan’ (That everything should be subject to her). The final line of Shakespeare’s lyric (‘To her let us garlands bring’) is modified in the German because of the rhyme scheme: it is easy to end a line in English with a stressed ‘ing’ syllable (sing, thing, bring etc.), but Bauernfeld was more constrained with -ang. However, Sang, lang, Klang (Saitenklang – Let her have garlands and the sound of stringed instruments) is an effective solution (and it sets the scene for the later comment about the song being ‘out of tune on the strings’). It also seems to have inspired Schubert to write a piano accompaniment that deliberately sounds like lute or guitar music.

☙

Original Spelling An Silvia Was ist Silvia, saget an, Daß sie die weite Flur preist? Schön und zart seh' ich sie nah'n, Auf Himmels Gunst und Spur weist, Daß ihr Alles unterthan. Ist sie schön und gut dazu? Reiz labt wie milde Kindheit; Ihrem Aug' eilt Amor zu, Dort heilt er seine Blindheit, Und verweilt in süßer Ruh. Darum Silvia tön', o Sang, Der holden Silvia Ehren; Jeden Reiz besiegt sie lang, Den Erde kann gewähren: Kränze ihr und Saitenklang!

Confirmed with Schubert’s probable source, William Shakspeare’s [sic] sämmtliche dramatische Werke übersetzt im Metrum des Originals II. Bändchen. Die beiden Edelleute von Verona, von Bauernfeld. Wien. Druck und Verlag von J. P. Sollinger. 1825, page 55; and with William Shakspeare’s sämmtliche dramatische Werke und Gedichte. Uebersetzt im Metrum des Originals in einem Bande nebst Supplement, […] Wien. Zu haben bei Rudolph Sammer, Buchhändler. Verlegt bei J. P. Sollinger, 1826, page 32.

Note: The song appears in Die beiden Edelleute von Verona, act 4, scene 2.

To see an early edition of the German text, go to page 55 [59 von 80] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ178566602