Ganymede

(Poet's title: Ganymed)

Set by Schubert:

D 544

[March 1817]

Wie im Morgenglanze

Du rings mich anglühst,

Frühling, Geliebter!

Mit tausendfacher Liebeswonne

Sich an mein Herze drängt

Deiner ewigen Wärme

Heilig Gefühl,

Unendliche Schöne!

Dass ich dich fassen möcht

In diesen Arm!

Ach an deinem Busen

Lieg’ ich, und schmachte,

Und deine Blumen, dein Gras

Drängen sich an mein Herz.

Du kühlst den brennenden

Durst meines Busens,

Lieblicher Morgenwind!

Ruft drein die Nachtigall

Liebend nach mir aus dem Nebeltal.

Ich komm! ich komme!

Wohin? Ach, wohin?

Hinauf! Hinauf strebt’s.

Es schweben die Wolken

Abwärts, die Wolken

Neigen sich der sehnenden Liebe.

Mir! Mir!

In eurem Schoße

Aufwärts!

Umfangend umfangen!

Aufwärts an deinen Busen,

Alliebender Vater!

In the glow of the morning, how

You are heating things up around me,

Spring, beloved!

With a thousand-fold loving bliss,

Pressing onto my heart is

Your eternal warmth’s

Sacred feeling,

Endless beauty!

If only I could get hold of you

In these arms!

Oh, on your breast

I am lying and languishing,

And your flowers, your grass

Are pushing themselves towards my heart.

You cool the burning

Thirst of my breast,

Lovely morning wind!

The nightingales are calling down

Lovingly towards me out of the misty valley.

I am coming, I am coming!

Where to? Oh, where to?

Up! There is a striving up.

The clouds are floating

Down, the clouds

Are bending down to this yearning love.

To me! To me!

Into your lap,

Upwards!

Embracing embraced!

Upwards to your breast,

All-loving father!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Arms and embracing Bending Chest / breast Clouds Eagles Eternity Father and child Fire Flowers Flying, soaring and gliding Ganymede Grass Hearts Heat Here and there High, low and deep Jupiter / Zeus Lack of water – thirst and drought Lap, womb (Schoß) Longing and yearning Metamorphosis Mist and fog Morning and morning songs Nightingales, Philomel Spring (season) Striving Valleys Wind

Now the beloved, since he receives all service from his lover, as if he were a god, and since the lover is not feigning, but is really in love, and since the beloved himself is by nature friendly to him who serves him, although he may at some earlier time have been prejudiced by his schoolfellows or others, who said that it was a disgrace to yield to a lover, and may for that reason have repulsed his lover, yet, as time goes on, his youth and destiny cause him to admit him to his society. For it is the law of fate that evil can never be a friend to evil and that good must always be friend to good. And when the lover is thus admitted, and the privilege of conversation and intimacy has been granted him, his good will, as it shows itself in close intimacy, astonishes the beloved, who discovers that the friendship of all his other friends and relatives is as nothing when compared with that of his inspired lover. And as this intimacy continues and the lover comes near and touches the beloved in the gymnasia and in their general intercourse, then the fountain of that stream which Zeus, when he was in love with Ganymede, called “desire” flows copiously upon the lover; and some of it flows into him, and some, when he is filled, overflows outside; and just as the wind or an echo rebounds from smooth, hard surfaces and returns whence it came, so the stream of beauty passes back into the beautiful one through the eyes, the natural inlet to the soul, where it reanimates the passages of the feathers, waters them and makes the feathers begin to grow, filling the soul of the loved one with love. So he is in love, but he knows not with whom; he does not understand his own condition and cannot explain it; like one who has caught a disease of the eyes from another, he can give no reason for it; he sees himself in his lover as in a mirror, but is not conscious of the fact. And in the lover's presence, like him he ceases from his pain, and in his absence, like him he is filled with yearning such as he inspires, and love's image, requited love, dwells within him; but he calls it, and believes it to be, not love, but friendship. Like the lover, though less strongly, he desires to see his friend, to touch him, kiss him, and lie down by him; and naturally these things are soon brought about. Now as they lie together, the unruly horse of the lover has something to say to the charioteer, and demands a little enjoyment in return for his many troubles; and the unruly horse of the beloved says nothing, but teeming with passion and confused emotions he embraces and kisses his lover, caressing him as his best friend; and when they lie together, he would not refuse his lover any favor, if he asked it; but the other horse and the charioteer oppose all this with modesty and reason. If now the better elements of the mind, which lead to a well ordered life and to philosophy, prevail, they live a life of happiness and harmony here on earth, self controlled and orderly, holding in subjection that which causes evil in the soul and giving freedom to that which makes for virtue; and when this life is ended they are light and winged, for they have conquered in one of the three truly Olympic contests. Neither human wisdom nor divine inspiration can confer upon man any greater blessing than this. Plato, Phaedrus, 255 - 6 (English translation by Harold N. Fowler, Harvard University Press 1925)

This extract from a speech attributed to Socrates is one of the clearest expositions of what has come to be called ‘Platonic love’, and it makes explicit reference to the old myth of the beautiful Phrygian lad Ganymede being taken up by Zeus to serve as the gods’ cup-bearer on Olympus. In this Platonic reading of the myth, Zeus’s attraction to the youth is no passing daliance and it cannot be ‘reduced’ to the erotic desire that led him to pursue Leda or Europa; his descent to earth and metamorphosis (taking on the form of an eagle in this case) is intended to lift Ganymede up to Olympus, where his continuing presence can be of vital service. What he offers to the immortal (but ageing) gods is all the potential and vibrancy of youth.

Goethe was just such a young man, bursting with creativity and passion, when he wrote this poem, so it is hardly surprising that he approached the myth not from the point of view of the god who decides to intervene and inspire the lad to new heights. He imagines what the experience was like from Ganymede’s own perspective as he suddenly found himself enraptured. This is an experience of ecstasy brought about by the most down to earth of feelings. It is a beautiful morning in spring and the reality of the earth in its fresh vibrancy is so intense that Ganymede finds himself being pulled ever more strongly towards it. As he lies on the ground he feels his breast pushing down against the counter-pressure of the spring-time grass and flowers. There is a mutual embrace as two living beings seem to become conscious of the common drive that has brought them together. In this moment of acceptance of the reality of the body, of the earthly, there is an eternity of spiritual fusion and ecstasy. Although the word ‘ecstasy’ means literally ‘standing apart’ or ‘outside’, the experience can only be reached by accepting rather than rejecting the physical dimension.

Goethe is using the old myth to challenge the predominant Christian tradition of dualism and asceticism, the idea that the body had to be overcome and rejected in order to attain spiritual bliss. Yet he is also rejecting another tradition in Western thought whereby Ganymede represented the idea of the value of static and unchanging beauty. In this way of viewing the story, we live in a corrupt, ageing society that has lost touch with purity and simplicity. Such was ancient Greece, such was Ganymede. Such, for Keats, was a Grecian Urn:

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, – that is all Ye know

on earth, and all ye need to know.”

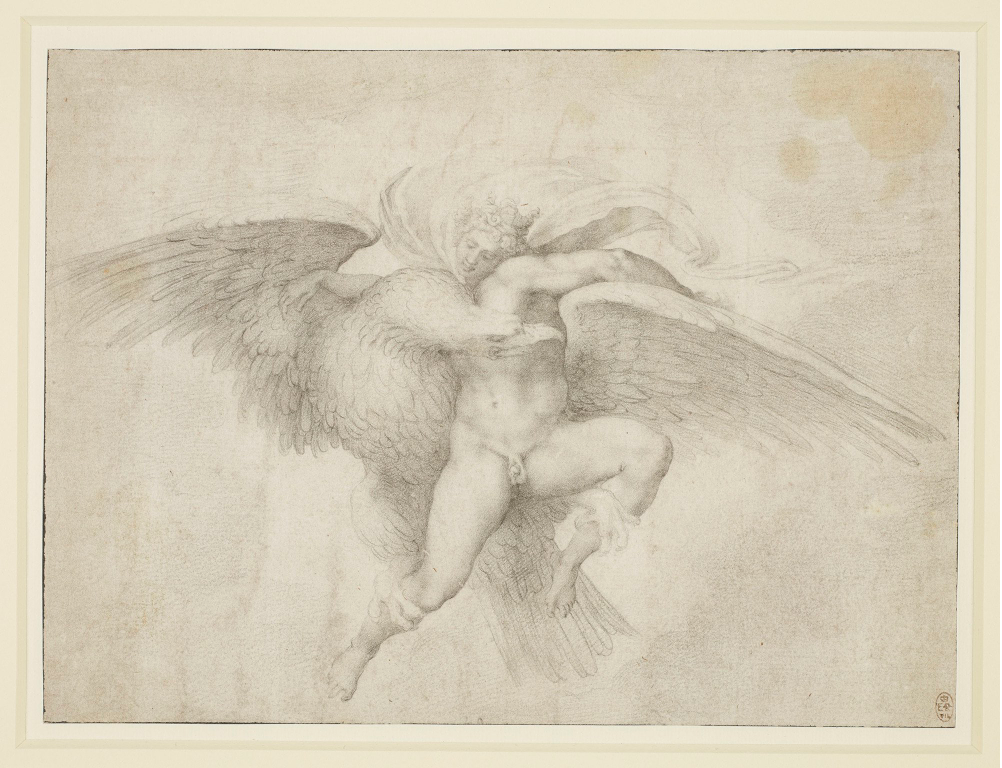

For Goethe, though, Ganymede does not represent any sort of ‘eternal’ youth or beauty. He is a living, breathing, feeling person. His attraction is that he is active and dynamic. He is not the passive form that is presented in some versions of the myth (e.g. Michelangelo’s drawing). He is not just someone that is embraced. He himself chooses to embrace. He responds to his environment and acts on it. As he lies on the earth’s breast and feels its heart beat against his, there is a mutual movement. The clouds descend and he rises. Both embraced and embracing, he finds himself in the lap of the god. The breast he was lying on is now experienced as the breast of the all-loving father. He has not been infantilised, though. He has not crawled back into the womb or reverted to passivity. The very reason why Ganymede has attracted the attention of Zeus is that he has reached puberty, he has left childhood and become old enough to act and make decisions. He has agency.

So it was for Goethe himself. As he reached maturity as a man and a writer, he found himself increasingly active rather than cut off from the world. Like Ganymede, he did not just lie on the grass, but he revelled in his environment with a total passion. He studied geology and mineralogy, botany and meteorology. He learnt to draw (and thereby to look). He embraced the physical and cultural world that he found himself in, but he also acted on it. He went on to supervise mining operations, and run a government, as well as to produce a seemingly endless stream of stimulating (and unpredictably creative) plays, novels and poems.

Of course the moment passed. The lad who wrote ‘Ganymede’ (in his early 20s) very soon became one of the old gods himself. However, he managed to avoid the fate of many venerable authors (such as Klopstock, perhaps) who lose touch with later generations. Goethe may have thought of himself as Zeus in his later years, but he knew enough about Greek mythology to know that the gods had to drink nectar, and that this should be served to them by Ganymede. He knew that he had to be on the lookout for the sort of creativity and youthful zest that would keep him alive and open to new experience.

Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen

[Photo: Malcolm Wren]

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Ganymed Wie im Morgenglanze Du rings mich anglühst, Frühling, Geliebter! Mit tausendfacher Liebeswonne Sich an mein Herz drängt Deiner ewigen Wärme Heilig Gefühl, Unendliche Schöne! Daß ich dich fassen möcht' In diesen Arm! Ach an deinem Busen Lieg' ich und1 schmachte, Und deine Blumen, dein Gras Drängen sich an mein Herz. Du kühlst den brennenden Durst meines Busens, Lieblicher Morgenwind! Ruft drein die Nachtigall Liebend nach mir aus dem Nebelthal. Ich komm', ich komme! Wohin? Ach, wohin? Hinauf! Hinauf strebt's. Es schweben die Wolken Abwärts, die Wolken Neigen sich der sehnenden Liebe. Mir! Mir! In euerm Schoße Aufwärts! Umfangend umfangen! Aufwärts an deinen Busen, Alliebender Vater! 1 Schubert added the word 'und' (and) here. Goethe's line was ' Lieg' ich, schmachte'.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Goethe’s Werke. Zweyter Band. Original-Ausgabe. Wien, 1816. Bey Chr. Kaulfuß und C. Armbruster.Stuttgart. In der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. Gedruckt bey Anton Strauß pages 92-93; with Goethe’s Werke. Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand. Zweyter Band. Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1827, pages 82-83; and with Goethe’s Schriften, Achter Band, Leipzig, bey Georg Joachim Göschen, 1789, pages 210-211.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 92 [100 von 350] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ223421905