Burial song

(Poet's title: Grablied)

Set by Schubert:

D 218

[June 24, 1815]

Er fiel den Tod für’s Vaterland,

Den süßen der Befreiungsschlacht,

Wir graben ihn mit treuer Hand

Tief, tief den schwarzen Ruheschacht.

Da schlaf, zerhauenes Gebein,

Wo Schmerzen einst gewühlt und Lust,

Schlug wild ein tötend Blei hinein

Und brach den Trotz der Heldenbrust.

Da schlaf gestillt, zerrissnes Herz,

So wunschreich einst, auf Blumen ein,

Die wir im veilchenvollen März

Dir in die kühle Grube streun.

Ein Hügel hebt sich über dir,

Den drückt kein Mal von Marmelstein.

Von Rosmarin nur pflanzen wir

Ein Pflänzchen auf dem Hügel ein.

Da sprosst und grünt so traurig schön,

Von deinem treuen Blut gedüngt,

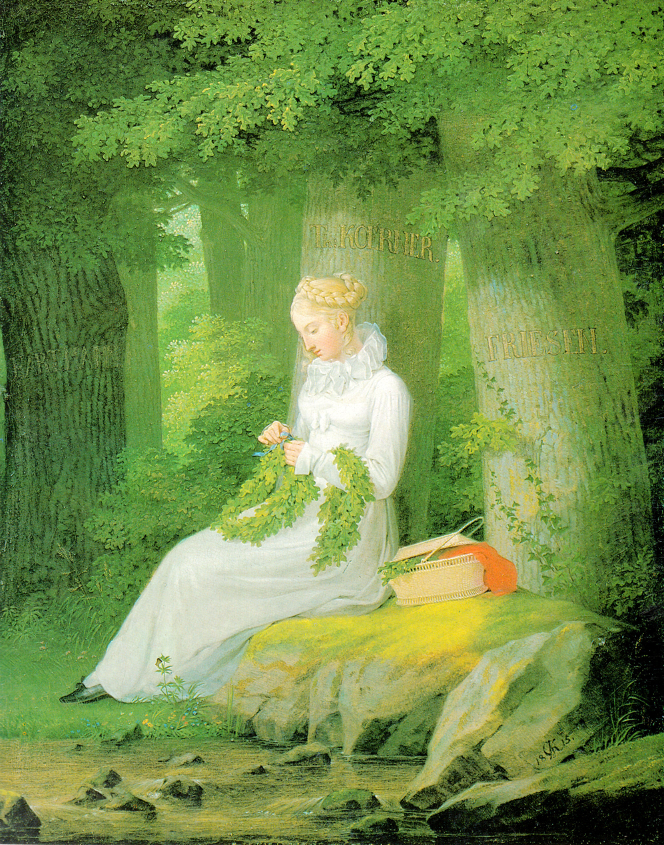

Man sieht zum Grab ein Mädchen gehn,

Das leise Minnelieder singt.

Die kennt das Grab nicht, weiß es nicht,

Wie der sie still und fest geliebt,

Der ihr zum Kranz, den sie sich flicht,

Den Rosmarin zum Brautkranz gibt.

He fell and died for the fatherland,

A sweet death in the battle for liberation,

We bury him with a faithful hand,

Deep, deep in the black peaceful shaft.

Sleep there, broken bones!

Where pain and pleasure once lodged

A deadly shot of lead burst rudely in

And broke the defiance of a heroic breast.

Sleep there and be calm, torn heart,

Once so rich in desires, on the flowers there

Which we collected in violet rich March

And have strewn in your cool trench.

A mound is being raised over you.

No marble monument will be imprinted there;

We shall just plant some rosemary –

A small plant on the mound.

As it germinates and becomes green it will be sadly beautiful,

Fertilized by your faithful blood.

A girl can be seen going to the grave

Gently singing songs of love.

Anyone who does not know the grave does not know

How he loved her quietly and devotedly,

He who allows her to make a wreath from

The rosemary; he gives it to her and she turns it into a bridal garland.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Black Blood Bones and skeletons Breaking and shattering Chest / breast Flowers Going to bed Graves and burials Green Guns Hearts High, low and deep Laments, elegies and mourning Lullabies Pouring, scattering and strewing Rosemary Sleep Sweetness Violets War, battles and fighting Weddings Wreaths and garlands

By 24th June 1815 Schubert would probably have heard the news about the Battle of Waterloo the previous week. The final defeat of Napoleon must have reminded him of his connnection with the Wars of Liberation and his settings of Körner from earlier in the year. His school friend Kenner (two of whose ballads Schubert had recently set: D 134 Ballade and D 209 Der Liedler) presumably handed him the manuscript of ‘Grablied’, dated 18th July 1813.

Who is being commemorated here? In July 1813 Austria had not yet declared war on France, and even Prussia and Russia had signed a ceasefire after the battles of spring 1813. Kenner is therefore probably writing about a representative (a sort of ‘unknown soldier’) of the ‘free fighters’, Lützow’s Black Hunters (cf. Schubert’s Körner settings D 204 Jägerlied and D 205 Lützows wilde Jagd), the most famous member of which was Theodor Körner (1791-1813), whom Schubert had met in Vienna in 1812 after a performance of a Gluck opera. Kenner’s burial song was written a month before Körner himself died in a skirmish and became the most famous of the young heroes of the Wars of Liberation. Anyone in Schubert’s circle listening to his setting of Kenner’s text would automatically associate it with Körner.

“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance” says Ophelia (Hamlet Act IV Scene 5), but that is only part of the story. As well as being a token of remembrance for the dead, rosemary also had connections with love and weddings. Brides also wore it, so a bridal garland could equally be a funeral wreath. The association is particularly clear in another Shakespeare play: when Juliet is found ‘dead’ on the morning of her wedding day, Friar Laurence instructs the Capulet family to dry up their tears and “stick your rosemary / On this fair corse, and as the custom is, / All in her best array bear her to church.”

Our bridal flowers serve for a buried corse,

And all things change them to the contrary.

Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet Act IV Scene 5

The connection between weddings and funerals is also explicit in Kenner’s burial song. Just as lullabies often make reference to death, elegies use the metaphor of sleep. The dead soldier is both being buried and being put to bed. He is told to sleep, and the text as a whole has the form of a lullaby, with the last stanza looking forward to the future (to the morning, to waking up to a new world). A bride that he loved devotedly (though she did not know it) will come to his bed and funeral wreaths will be turned into bridal garlands.

In case all of this feels a little too symbolic and abstract (with the bride as something like the Future being faithful to the Fallen Hero or something of the sort), the poet forces us to be more down to earth (actually down in the earth). We are spared none of the gory details of the soldier’s wounds, with hacked bones as well as a slug of lead lodged somewhere. When the poet refers to the soldier’s broken heart (zerissenes Herz) this might not just be a figure of speech: it has probably been ripped apart physically. The blood that is fertilizing the rosemary is all too real. The mourners are actually burying him, ‘with faithful hands’: they are lifting the mangled corpse and doing the dirty work of putting it into a recently dug trench. He has died for the fatherland, and now he is in that land, part of it, embedded. His molecules will be recycled into the plants that grow on his grave. The planting of rosemary is not just ‘for remembrance’; it turns his grave into a flower bed and connects the bed of marriage with the fertility that comes from decomposition. His death is part of the new life that is growing out of the wars of liberation.

☙

Original Spelling Grablied Er fiel den Tod für's Vaterland, Den süßen der Befreiungsschlacht; Wir graben ihn mit treuer Hand Tief tief den schwarzen Ruheschacht. Da schlaf' zerhauenes Gebein: Wo Schmerzen einst gewühlt und Lust, Schlug wild ein tödtend Blei hinein, Und brach den Trotz der Heldenbrust. Da schlaf' gestillt, zerriß'nes Herz So wunschreich einst, auf Blumen ein, Die wir im veilchenvollen März Dir in die kühle Grube streu'n. Ein Hügel hebt sich über dir, Den drückt kein Maal von Marmorstein. Von Rosmarin nur pflanzen wir Ein Pflänzchen auf dem Hügel ein. Da sproßt und grünt so traurig schön, Von deinem treuen Blut gedüngt: Man sieht zum Grab ein Mädchen geh'n, Das leise Minnelieder singt. - Die kennt das Grab nicht, weiss es nicht, Wie der sie still und fest geliebt, Der ihr zum Kranz, den sie sich flicht, Den Rosmarin zum Brautkranz gibt.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Huldigung den Frauen. Ein Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1828. Herausgegeben von J.F. Castelli. Sechster Jahrgang. Wien, bey Tendler und von Manstein, pages 43-44; and with Oberösterreichisches Jahrbuch für Literatur und Landeskunde. Erster Jahrgang. 1844. Herausgegeben von Karl Adam Kaltenbrunner. Linz, 1844. Verlag von Vincenz Fink, pages 192-193.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 43 [Erstes Bild 57] here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb11044871