We are not dealing with a static image here. Snakes writhe and wriggle, they twist and turn. The hair of the Furies that pursued Orestes to Tauris (D 548) was made of entwined snakes, symbolising the relentless agitation and disturbance that afflicted him.

Other texts that include references to snakes make this connection with inner turmoil even more explicit. Memnon (D 541) explains that there is a serious misunderstanding on the part of the visitors who come to hear his song every morning. Although the tourists believe that he is singing joyfully to greet the dawn he is in fact experiencing an unutterable torment as his yearning to escape his earthly prison tears him apart.

In mir, nach dem des Todes Arme langen,

In dessen tiefstem Herzen Schlangen wühlen,

Genährt von meinen schmerzlichen Gefühlen,

Fast wütend durch ein ungestillt Verlangen:

Mit dir, des Morgens Göttin, mich zu einen

Inside me - to whom death is reaching out its arms,

Within the depth of whose heart serpents are burrowing;

Nourished by my painful feelings -

Almost driven to distraction by a single, unappeased craving:

To unite myself with you, goddess of the morning

Mayrhofer, Memnon D 541

The narrator in Müller’s Winterreise is in a totally different situation but shares a similar inner agony. Whereas Memnon is a monumental unmoving and unmovable statue, Müller’s winter traveller keeps moving outwardly. When, one evening, he settles down to rest in a charcoal burner’s hut he begins to feel the physical wounds which had been numb earlier. More significantly, perhaps, he realises that there can be no rest for his soul. In the still of the night he becomes aware of the twisting serpent that is injecting its venom into his throbbing heart.

In eines Köhlers engem Haus

Hab Obdach ich gefunden;

Doch meine Glieder ruhn nicht aus:

So brennen ihre Wunden.

Auch du, mein Herz, in Kampf und Sturm

So wild und so verwegen,

Fühlst in der Still erst deinen Wurm

Mit heißem Stich sich regen.

In the narrow house of a charcoal burner

Is where I have found shelter;

Yet my limbs cannot settle down:

Their wounds are burning so much.

You too, my heart, in battle and storm

So savage and so foolhardy,

In this silence it is the first time you have felt your serpent

Move with its hot venom!

Müller, Rast (Winterreise) D 911/10

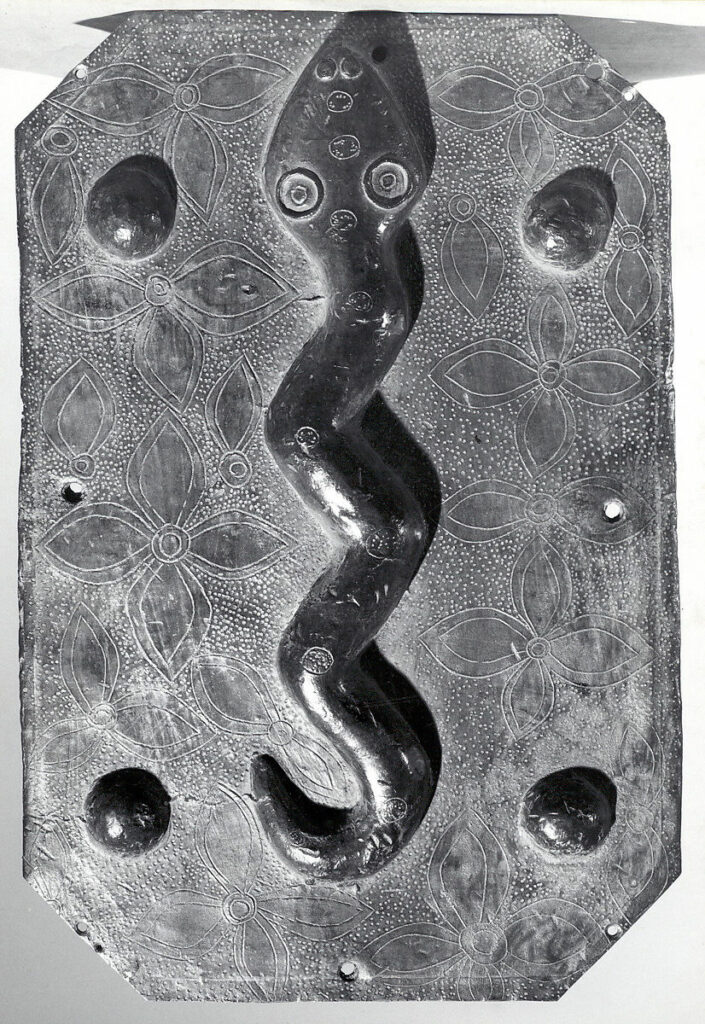

Schlangengleich gewunden / Twisted like a snake

It seems obvious that twisting and writhing embody inner contortions and disturbances. This may be an element in the long-standing human aversion to snakes in general. It is therefore unusual for a poet to turn the image of an entwined snake into something positive, but both Goethe and Schlegel managed to do this when comparing meandering rivers (both physical and metaphorical) to curling serpents.

Wie rein Gesang sich windet

Durch wunderbarer Saitenspiele Rauschen,

Er selbst sich wieder findet,

Wie auch die Weisen tauschen,

Dass neu entzückt die Hörer ewig lauschen.

So fließet mir gediegen

Die Silbermasse, schlangengleich gewunden,

Durch Büsche, die sich wiegen

Vom Zauber süß gebunden,

Weil sie im Spiegel neu sich selbst gefunden.

In the same way that a pure song meanders

Through the miraculous resonance of strings as they are played

And finds itself again,

And just as the melodies interweave

So that the listeners, newly enraptured, continue to pay attention:

That is how, for me, the river flows so solidly

In a silver mass, twisted around like a snake,

Through bushes which sway

As they are sweetly bound up in the magic

Since they have found themselves anew in the mirror.

Friedrich von Schlegel, Der Fluss D 693

Schlegel is here attempting to capture the mystery of the poet’s direct perception of the harmony of nature bound up in the complexity and distortions of everyday reality. Within the noise of the world the sensitive soul is able to detect an emerging harmony, and hidden in the reflections of a twisting river the poet can detect a simpler, underlying reality. The river meanders and curls like a snake, seemingly lost and directionless, capturing and reflecting the swaying vegetation on the banks, yet it is only within this movement that the unchanging essence of the world can be detected.

Goethe’s Mahomets Gesang (D 549, D 721) from the early 1770’s uses similar snake / river imagery to explore the nature of spiritual and aesthetic perception and creativity, but with the focus explicitly on ‘movement’. The image of a river, bringing together convergent streams, then meandering, snake-like across the plains is applied to at least two cultural ‘movements’: the rise and spread of Islam in the lifetime of the prophet Mohammed and the new poetry that this text embodies, ‘Sturm und Drang’ in the 1770’s. Again, the apparent aimlessness of the river is shown to be a delusion. A wider view allows us to see that the movement is purposeful and leading us to a significant destiny / destination.

Drunten in dem Tal

Unter seinem Fußtritt werden Blumen,

Und die Wiese

Lebt von seinem Hauch.

Doch ihn hält kein Schattental,

Keine Blumen,

Die ihm seine Knie umschlingen,

Ihm mit Liebes-Augen schmeicheln:

Nach der Ebne dringt sein Lauf

Schlangenwandelnd.

Bäche schmiegen

Sich gesellig an. Nun tritt er

In die Ebne silberprangend,

Und die Ebne prangt mit ihm.

Und die Flüsse von der Ebne

Und die Bäche von den Bergen,

Jauchzen ihm und rufen: Bruder,

Bruder, nimm die Brüder mit,

Mit zu deinem alten Vater,

Zu dem ewgen Ocean

Further down in the valley appear

Flowers under his footprint,

And the meadow

Lives on the breath of the spring.

But no shady valley can hold on to him,

No flowers

Clinging around his knees

Flattering him with loving eyes:

His course is set for the plains,

Twisting like a snake.

Brooks snuggle

Up gregariously. Now he steps

Onto the plain, resplendent with silver,

And the plain shares his splendour,

And the rivers of the plain

And the brooks from the mountains

Cheer him on and call: Brother!

Brother, take your brothers with you,

Along with you to your old father,

To the eternal ocean

Goethe, Mahomets Gesang D 549, D 721

☙

Descendant of:

AnimalsTexts with this theme:

- Memnon, D 541 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Orest, D 548 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Mahomets Gesang, D 549, D 721 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Fluss, D 693 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Rast, D 911/10 (Wilhelm Müller)