Orestes

(Poet's title: Orest)

Set by Schubert:

D 548

[March 1817]

Ist dies Tauris, wo der Eumeniden

Wut zu stillen Pythia versprach.

Weh! die Schwestern mit den Schlangenhaaren

Folgen mir vom Land der Griechen nach.

Rauhes Eiland, kündest keinen Segen,

Nirgends sprosst der Ceres milde Frucht.

Keine Reben blühn, der Lüfte Sänger

Wie die Schiffe meiden diese Bucht.

Steine fügt die Kunst nicht zu Gebäuden,

Zelte spannt des Skythen Armut sich,

Unter starren Felsen, rauhen Wäldern

Ist das Leben einsam, schauerlich.

Und hier soll, so ist ja doch ergangen

An den Flehenden der heilige Spruch,

Eine hohe Priesterin Dianens

Lösen meinen und der Väter Fluch.

Is this Tauris, where the Eumenides’

Fury is to be stilled, according to the promise of the Delphic oracle?

Alas, the sisters with snakes for their hair

Have followed me here from the land of the Greeks!

Bleak island, you offer no blessing:

The gentle fruit of Ceres never sprouts here.

No vines blossom, singers in the air,

Like ships, avoid this bay.

Art does not structure these stones into buildings,

The poverty of the Scythians has stretched out tents;

Amongst rigid cliffs, primeval forests,

Life is lonely, horrific!

“And it is here,” so it has been proclaimed

To the suppliant in the sacred pronouncement:

“That one of the high priestesses of Diana

Will lift the curse on me and my forefathers.”

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Air The ancient world Anger and other strong emotions Artemis / Diana Birds Brothers and sisters Buildings and architecture By water – beaches and general Corn and cornfields Curses Father and child Flowers Fruit Germination, shoots and sprouting Hair Mother and child Mountains and cliffs Rough and smooth Islands Ships Snakes Vengeance Wine and vines Woods – large woods and forests (Wald)

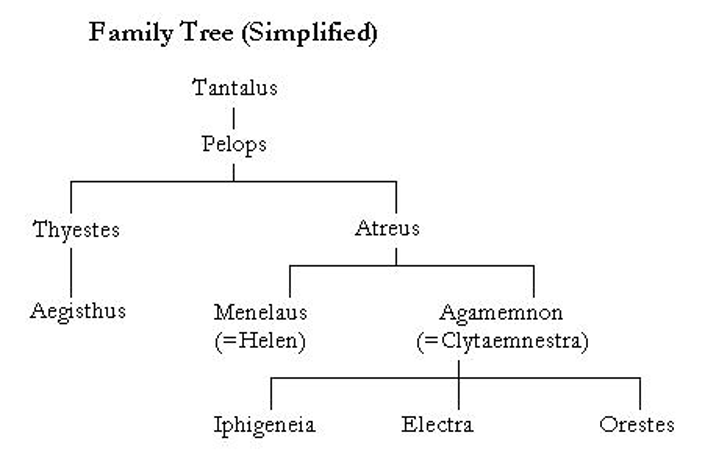

Orestes has landed on the coast of Tauris (the Crimean peninsula) but is unaware that the High Priestess of Diana (Artemis) has a duty to offer up such shipwrecked visitors as a human sacrifice. He is equally unaware that the same High Priestess is no other than his long-lost sister Iphigenia. Her disappearance had been part of a terrible series of family events (details vary according to different ancient writers, of course):

- As King Agamemnon set out for the Trojan War to reclaim his sister-in-law Helen, he incurred the wrath of the goddess Artemis. She demanded that he sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia at Aulis, but at the last moment Artemis / Diana accepted the sacrifice of a deer instead and whisked Iphigenia away to Tauris as her priestess there.

- Agamemnon’s wife Klytemnestra believed that her daughter Iphigenia had been killed by Agamemnon and plotted with her lover Aegisthus to murder him on his return from the war.

- Iphigenia’s sister Elektra was determined that Agamemnon’s murder be avenged, and when her brother Orestes returned she urged him to kill Klytemnestra and Aegisthus.

- Having done so, Orestes found himself pursued by the Euminedes, the avenging furies (with snakes for their hair). He therefore appealed to Apollo’s oracle at Delphi for guidance on how to lift the curse on his family and was directed towards Tauris.

Mayrhofer would have expected his original readers to be familiar with this background. In Vienna in the early 19th century the stories were kept alive in performances of Goethe’s play Iphigenie auf Tauris (revised version 1787) and Gluck’s opera Iphigénie en Tauride (1779). The poet has chosen the moment in both of these versions where Orestes makes his first appearance (the beginning of Act II in Goethe’s play and the end of Act I in Gluck’s opera).

Mayrhofer’s readers, most of whom had received a ‘classical’ education and as ‘civilised’ inhabitants of a modern city (Vienna), would have shared Orestes’ bias in favour of the Greek approach to the ‘primitive’ land of Tauris. It has taken historians, anthropologists and archaeologists generations to break down the prejudice against the Scythians established by Herodotus and others. We are now aware of the astonishing culture of these nomadic groups (not least as great metal workers), but the ancient Greeks were unable to see beyond the lack of permanent stone buildings. The Scythians’ bits of canvas appeared to be makeshift ways of coping rather than a supremely well-adapted solution to the demands of a life spent on horseback. Orestes, as he lands in Tauris, sees this lack of ‘culture’ reflected in the barrenness of nature. The song birds he is familiar with seem to avoid the area, there are no vines and the fruit of Ceres (cereals!) is absent. What this means is that he has travelled north to an area where there is no long tradition of agriculture, but Orestes cannot help but see the place as a contrast to ‘civilised’ Greece.

His first impression is that life in such a raw environment must be ‘lonely, horrific’. Are we supposed to pick up the irony here? This condescending spokesman of advanced culture thinks that he represents the values of living in society, yet he has just killed his mother and his uncle (because they had murdered his father) and he is about to be killed by his sister. He is somehow surprised that his journey across the Black Sea has not allowed him to escape from the Furies that have been pursuing him. Since they are nothing other than a way of referring to his conscience or to the post-traumatic stress that is now part of his being, it is hardly surprising that they cannot be left ‘at home’. However, if he is to recover, if ‘the curse’ is to be ‘lifted’ he has to travel to somewhere ‘other’. It is only on some (emotionally or spiritually) ‘distant’ or ‘other’ shore that he will find a solution. As he looks around his new environment he is not at all sure that such a resolution is possible. Can he rely on the notoriously ambiguous ‘prophecies’ of the oracle?

We might not all have had quite such extreme experiences, but we do not have to be matricides to feel that our life is cursed. Like Orestes, we try to do good, we have the best of intentions, but somehow things do not get sorted out or they get even worse. Like him, we feel the need to escape from the pursuing furies.

☙

Original Spelling, Note on the Text and the Title Orest Ist dies Tauris, wo der Eumeniden Wuth zu stillen, Pythia versprach? Weh, die Schwestern mit den Schlangenhaaren Folgen mir vom Land der Griechen nach! Rauhes Eyland, kündest keinen Segen: Nirgends sproßt der Ceres milde Frucht. Keine Reben blühn, der Lüfte Sänger, Wie die Schiffe, meiden diese Bucht. Steine fügt die Kunst nicht zu Gebäuden, Zelte spannt des Scythen Armuth sich; Unter starren Felsen, rauhen Wäldern Ist das Leben einsam, schauerlich! »Und hier soll,« so ist ja doch ergangen An den Flehenden der heilige Spruch: »Eine hohe Priesterin Dianens Lösen meinen und der Väter Fluch.« This song was formerly known as Orest auf Tauris (Orestes on Tauris). In the collected edition of Mayrhofer's works the poem is called Der landende Orest (Orestes coming ashore). There are some minor differences between the text as set by Schubert and as it appeared in the 1824 edition of Mayrhofer's poems. It is impossible to know if Schubert made the changes as he composed his setting or if he was working from an earlier draft of the text. The printed version appears below, with the differences in bold. Dieses Tauris? wo der Eumeniden Wuth zu stillen, Pythius versprach? Weh, die Schwestern mit den Schlangenhaaren Folgen mir vom Land der Griechen nach! Rauhes Eyland, kündest keinen Segen: Nirgends sproßt der Ceres goldne Frucht. Keine Reben blühn, der Lüfte Sänger, Wie die Schiffe, meiden diese Bucht. Steine fügt die Kunst nicht zu Gebäuden, Zelte spannt des Scythen Armuth sich; Unter starren Felsen, rauhen Wäldern Ist das Leben einsam, schauerlich! »Allhier soll,« so ist ja doch ergangen An den Flehenden der heilige Spruch: »Soll die Bogenspannerin Diana Lösen deinen und der Väter Fluch.«

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 159.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 159 [173 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902