Drinking song

(Poet's title: Trinklied)

Set by Schubert:

D 888

[July 1826]

Bachus, feister Fürst des Weins,

Komm mit Augen hellen Scheins,

Unsre Sorg ersäuf dein Fass,

Und dein Laub uns krönen lass,

Füll uns, bis die Welt sich dreht,

Füll uns, bis die Welt sich dreht.

Bacchus, plump Prince of Wine,

Come with brightly shining eyes,

Let our cares be drowned in your vat,

And let us be crowned with your leaves.

Fill us, until the world revolves,

Fill us, until the world revolves.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Bacchus Drinking songs Emptiness and fullness Eyes Leaves and foliage Wine and vines

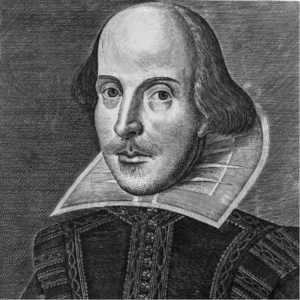

Act II Scene 7 of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (written c. 1607) is set on board Pompey’s galley, moored at the foot of Mount Misena (near modern Naples). Pompey (son of Pompey ‘the Great’) is entertaining Enobarbus, Octavius Caesar and Mark Antony, who has been telling his stories about Egypt:

ENOBARBUS [to Antony] Ha, my brave emperor, Shall we dance now the Egyptian Bacchanals And celebrate our drink? POMPEY Let's ha't, good soldier. ANTONY Come, let's all take hands Till that the conquering wine hath steeped our sense In soft and delicate Lethe. ENOBARBUS All take hands. Make battery to our ears with the loud music, The while I'll place you; then the boy shall sing. The holding every man shall beat as loud As his strong sides can volley. Music plays. Enobarbus places them hand in hand. The Song BOY Come, thou monarch of the vine, Plumpy Bacchus with pink eyne! In thy vats our cares be drowned; With thy grapes our hairs be crowned. ALL Cup us till the world go round! Cup us till the world go round! CAESAR What would you more? Pompey, good night. Good brother, Let me request you off. Our graver business Frowns at this levity. Gentle lords, let's part. You see we have burnt our cheeks. Strong Enobarb Is weaker than the wine, and mine own tongue Splits what it speaks. The wild disguise hath almost Anticked us all. What needs more words? Good night. Good Antony, your hand. POMPEY I'll try you on the shore. ANTONY And shall, sir. Give's your hand. POMPEY O, Antony, you have my father's house. But what? We are friends! Come down into the boat. ENOBARBUS Take heed you fall not. [Exeunt] William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra Act II Scene 7 lines 103 - 131 Edited by John Wilders (The Arden Shakespeare 1995)

At first glance this drinking song seems to be totally formulaic. There is an invocation of Bacchus / Dionysius, the god of wine and frenzy. His followers (Bacchantes) wear wreaths of vine leaves for the bacchanal and they decide to drown their sorrows in the contents of the vat or barrel. However, we need to remember that the refrain ‘Cup us till the world go round!’ had a stronger force in the early 17th century than it does for us. As Shakespeare was writing Antony and Cleopatra in London Galileo Galilei in Padua was using his telescopic observations of Venus and Jupiter to provide empirical support for a heliocentric model of the universe. A generation earlier Copernicus had published De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (On the revolution of the heavenly spheres, 1543), to widespread ridicule. Few of Shakespeare’s contemporaries could cope with the idea of an earth that was revolving, either on its own axis or around the sun, let alone both. The idea of getting so drunk that the earth actually went round would have turned their heads.

We also need to bear in mind the context in which the German translation was made (it was published in Vienna in 1825) and set to music by Schubert (in July 1826). This was in the period after the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819, in which Metternich (the Chancellor of Austria) had persuaded rulers throughout the German speaking lands to crack down on student associations. All universities were being heavily policed and all male clubs were seen as potential sources of agitation and rebellion. The effect was that innocent groups of lads meeting for a drink all too easily found themselves in trouble. Lifting a glass and wanting the world to turn around was literally inviting revolution.

☙

Shakespeare (First Folio text, 1623)

Come thou Monarch of the Vine,

Plumpie Bacchus, with pinke eyne:

In thy Fattes our Cares be drown’d,

With thy Grapes out haires be Crown’d.

Cup us till the world go round,

Cup us till the world go round.

Grünbühel and Bauernfeld

Bachus, feister Fürst des Weins,

Komm mit Augen hellen Scheins,

Uns’re Sorg’ ersäuf’ dein Faß,

Und dein Laub uns krönen laß.

Füll’ uns, bis die Welt sich dreht,

Füll’ uns, bis die Welt sich dreht!

Back translation

Bacchus, plump Prince of Wine,

Come with brightly shining eyes,

Let our cares be drowned in your vat,

And let us be crowned with your leaves.

Fill us, until the world revolves,

Fill us, until the world revolves.

☙

Original Spelling Trinklied Bachus, feister Fürst des Weins, Komm mit Augen hellen Scheins, Uns're Sorg' ersäuf' dein Faß, Und dein Laub uns krönen laß. Füll' uns, bis die Welt sich dreht, Füll' uns, bis die Welt sich dreht!

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, William Shakspeare’s [sic] sämmtliche dramatische Werke übersetzt im Metrum des Originals. XXXVI. Bändchen. Antonius und Cleopatra, von Ferd. v. Mayerhofer. 11. neue Uibersetzung. Wien. Druck und Verlag von J. P. Sollinger. 1825, page 47; and with William Shakspeare’s sämmtliche dramatische Werke und Gedichte. Uebersetzt im Metrum des Originals in einem Bande nebst Supplement, […] Wien. Zu haben bei Rudolph Sammer, Buchhändler. Verlegt bei J. P. Sollinger, 1826, page 864.

Note: The song appears in Antonius und Cleopatra, act 2, scene 7.

Schubert wrote a repeat sign in his autograph, thus demanding that the same single stanza be sung twice. Diabelli, the editor of the posthumous first edition (1850), misinterpreted this repeat sign and added an additional stanza, presumably written by Friedrich Reil, which has been retained in the Peters edition but not in the complete editions.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 47 [55 von 126] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ178572900