To Diana in her fury

(Poet's title: Der zürnenden Diana)

Set by Schubert:

D 707

[December 1820]

Ja, spanne nur den Bogen, mich zu töten,

Du himmlisch Weib! im zürnenden Erröten

Noch reizender. Ich werd es nie bereuen,

Dass ich dich sah am blühenden Gestade

Die Nymphen überragen in dem Bade,

Der Schönheit Funken in die Wildnis streuen.

Den Sterbenden wird noch dein Bild erfreuen.

Er atmet reiner, er atmet freier,

Wem du gestrahlet ohne Schleier.

Dein Pfeil, er traf; doch linde rinnen

Die warmen Wellen aus der Wunde;

Noch zittert vor den matten Sinnen

Des Schauens süße letzte Stunde.

Yes, just stretch your bow in order to kill me

Oh heavenly woman! In your raging blushes

You are even more enticing. I shall never regret it:

The fact that I saw you on the blossoming river bank

Outshining the nymphs as they bathed;

You were scattering sparks of beauty over the wilderness.

Although I am dying I shall nevertheless take delight in your image.

He can breathe more purely, he can breathe more freely,

He on whom you shone without your veil.

Your arrow, it has struck – yet it is gentle, this pouring out of

Warm waves from the wound:

My faint senses are still trembling

From what I have seen in this sweet, final hour.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Anger and other strong emotions Artemis / Diana Blood Bows and arrows Breath and breathing By water – river banks Hunters and hunting Nymphs Red and purple Sweetness Veils Waves – Welle

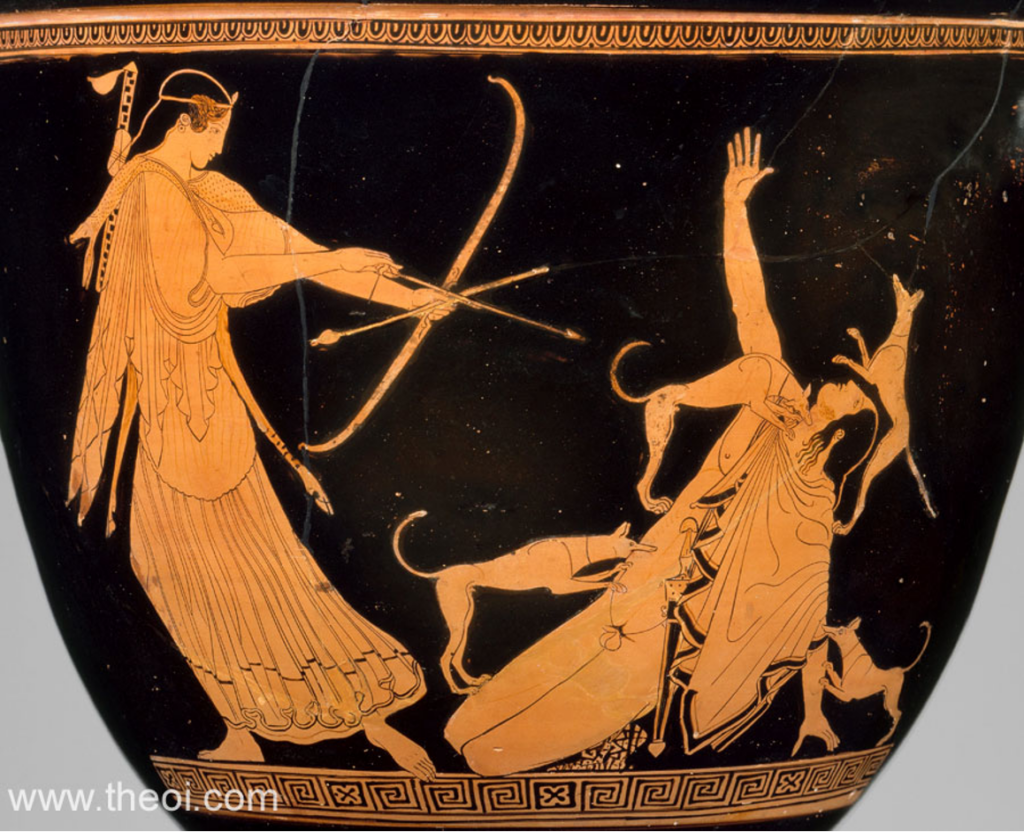

Actaeon and Diana (from Ovid, Metamporphoses Book 3) There was a valley there called Gargaphie, dense with pine trees and sharp cypresses, sacred to Diana of the high-girded tunic, where, in the depths, there is a wooded cave, not fashioned by art. But ingenious nature had imitated art. She had made a natural arch out of native pumice and porous tufa. On the right, a spring of bright clear water murmured into a widening pool, enclosed by grassy banks. Here the woodland goddess, weary from the chase, would bathe her virgin limbs in the crystal liquid. Having reached the place, she gives her spear, quiver and unstrung bow to one of the nymphs, her weapon-bearer. Another takes her robe over her arm, while two unfasten the sandals on her feet. Then, more skilful than the rest, Theban Crocale gathers the hair strewn around her neck into a knot, while her own is still loose. Nephele, Hyale, Rhanis, Psecas and Phiale draw water, and pour it over their mistress out of the deep jars. While Titania is bathing there, in her accustomed place, Cadmus’s grandson, free of his share of the labour, strays with aimless steps through the strange wood, and enters the sacred grove. So the fates would have it. As soon as he reaches the cave mouth dampened by the fountain, the naked nymphs, seeing a man’s face, beat at their breasts and filling the whole wood with their sudden outcry, crowd round Diana to hide her with their bodies. But the goddess stood head and shoulders above all the others. Diana’s face, seen there, while she herself was naked, was the colour of clouds stained by the opposing shafts of sun, or Aurora’s brightness. However, though her band of nymphs gathered in confusion around her, she stood turning to one side, and looking back, and wishing she had her arrows to hand. She caught up a handful of the water that she did have, and threw it in the man’s face. And as she sprinkled his hair with the vengeful drops she added these words, harbingers of his coming ruin, ‘Now you may tell, if you can tell that is, of having seen me naked!’ Without more threats, she gave the horns of a mature stag to the head she had sprinkled, lengthening his neck, making his ear-tips pointed, changing feet for hands, long legs for arms, and covering his body with a dappled hide. And then she added fear. English translation by Anthony S. Kline, 2000 http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm#476975721

Ovid was writing in Latin (in the first decade of the first century CE), so for him the goddess was the Roman ‘Diana’ rather than the older ‘Artemis’, the virgin fertility goddess who resided by streams and in woods in the company of deer. However, the story he was telling was already well established in Greek literature (e.g. Apollodorus). Although Ovid’s prime interest in the story was the climax in which Actaeon the hunter is turned into a stag and then himself becomes the hunted as his dogs tear him apart, Mayrhofer downplays the idea of the tables being turned. He freezes the narrative at the moment when Diana turns to look for her bow and he imagines Actaeon’s response to her fury. The speaker welcomes her arrow and dies in bliss, accepting that his life has no more meaning now that he has beheld the goddess in all of her beauty and her wrath.

Mayrhofer was clearly attracted to figures like this who willingly embraced annihilation (Schubert had already set a number of his poems on this theme, e.g. D 585 Atys, D 699 Der entsühnte Orest, D 700 Freiwilliges Versinken). What is unusual here, though, is the combination of sex and death. Atys had castrated himself in order to avoid such erotic encounters with his goddess (Cybele) but Actaeon’s orgasmic expiration is the ultimate Liebestod. He has seen Diana unveiled, he has seen her in all her flushing redness and now he is in turn penetrated as she tautens her bowspring and releases the arrow. This produces a wound (a vagina?) that oozes blood. Forget the antlers, this is the true metamorphosis that Actaeon undergoes as he loses his manhood.

National Galleries of Scotland

Attic red figure vase painting c. 470 BCE

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text Der zürnenden Diana Ja, spanne nur den Bogen, mich zu tödten, Du himmlisch Weib! im zürnenden1 Erröthen Noch reitzender. Ich werd' es nie bereuen: Daß ich dich sah am blühenden2 Gestade Die Nymphen überragen in dem Bade; Der Schönheit Funken in die Wildniß streuen. Den Sterbenden wird noch dein Bild erfreuen. Er athmet reiner, er3 athmet freyer, Wem du gestrahlet ohne Schleyer. Dein Pfeil, er traf - doch linde rinnen Die warmen Wellen aus der Wunde: Noch zittert vor den matten Sinnen Des Schauens süße letzte Stunde. 1 When the poem was published in 1824 the word here was ´zornigen´(angry). It is impossible to know whether Schubert made the change when he set the text to music or if he was working from an earlier draft of Mayrhofer´s text 2 Mayrhofer 1824: ´buschigen´(bushy) 3 Mayrhofer 1824 omits ´er´(he) here

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 158.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 158 [172 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902