The enraged bard

(Poet's title: Der zürnende Barde)

Set by Schubert:

D 785

[February 1823]

Wer wagt’s, wer wagt’s, wer wagt’s,

Wer will mir die Leier zerbrechen,

Noch tagt’s, noch tagt’s, noch tagt’s,

Noch glühet die Kraft, mich zu rächen.

Heran, heran, ihr alle,

Wer immer sich erkühnt,

Aus dunkler Felsenhalle

Ist mir die Leier gegrünt.

Ich habe das Holz gespalten

Aus riesigem Eichenbaum,

Worunter einst die Alten

Umtanzten Wodans Saum.

Die Saiten raubt’ ich der Sonne,

Den purpurnen, glühenden Strahl,

Als einst sie in seliger Wonne

Versankt in das blühende Tal.

Aus alter Ahnen Eichen,

Aus rotem Abendgold

Wirst Leier du nimmer weichen,

So lang die Götter mir hold.

Who dares, who dares, who dares,

Who wants to shatter my lyre,

It is still daylight, it is still daylight, it is still daylight,

The strength is still glowing to allow me to take revenge.

Come on, come on, all of you,

Whoever wants to make so bold,

Out of the dark rocky cliffs

My lyre flourished for me.

I split the wood

Out of a giant oak tree,

Under which the ancients used to

Dance around Wotan’s hem.

I stole the strings from the sun,

The crimson, glowing beam,

When in blissful ecstasy it used to

Sink into the blossoming valley.

Made from the oak of our ancient ancestors,

Made from the red gold of evening,

Lyre, you will never lose your power

As long as the gods look favourably on me.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Anger and other strong emotions Bards and minstrels Evening and the setting sun Gold Lyres Oak trees Rays of light Red and purple Valleys

What sort of a challenge is this? What has made this bard so furious? He is in the mood to take on all comers, using the sort of language that is more common in boxing and wrestling than in minstrelsy. Yes, there IS competitive barding: Ossian describes such events and Wagner’s Tannhäuser portrays the medieval Minnesingers as indulging in song competitions. Eisteddfods remain popular, but none of these, not even the Eurovision Song Contest, has ever aroused the sort of raw fury captured in Bruchmann’s text. Even Elvis Presley and Mick Jagger at their testosterone-fuelled best, strutting with their lyres (well, their guitars), were only exuberant, never aggressive.

For this infuriated bard the lyre is more of a spear or lance than a musical instrument. The references to it being plucked from a giant oak and to worship of Odin / Wotan takes us into the world of ‘The Golden Bough‘[1], where the protector of the sacred bough reigns until he is challenged and defeated by a younger, fitter, more fertile guardian. We might think of the scene in Act Three of Wagner’s Siegfried in which the young hero’s sword cuts through the old god’s spear, or the clash of light sabres in Star Wars: The Force Awakens with Han Solo and Kylo Ren. The poet appears to be assuming the role of priest in a sacred cult devoted to preserving an ancient mystery or force.

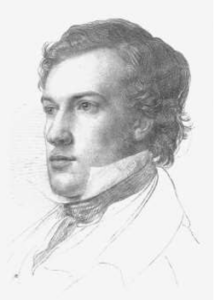

If it is a mystery, by definition we cannot know what was actually driving the poet’s anger. However, we do know about an incident in which Bruchmann, the author of this poem, found himself at odds with the authorities and this might hold the key to the text. On 20th January 1820 Bruchmann, Johann Senn, Franz Schubert, Josef Ludwig von Streinsberg and Johann Baptist Zechenter were arrested as part of a general crackdown on student societies (after the so-called Carlsbad Resolutions of 1819). Although Bruchmann got off lightly in comparison with Senn (who was removed from Vienna) we can imagine that he saw the whole thing as an outrageous assault on the freedom of thought and the freedom of assembly. He and his friends had a clear understanding of how censorship worked in Metternich’s Austria (after all, one of Schubert’s closest friends, Johann Mayrhofer, worked as a government censor). What harm had he been doing reciting poetry /playing his lyre amongst friends on that winter’s night? We can easily imagine his outrage and his increasing determination to take revenge on the evil powers that had decided to send a letter to his rich father about the bad company he was keeping. He would defend himself. He would defend the role of the artist in society. He would get his revenge. He would write a lyric and his friend Schubert would set it to music. And that is just what happened. “KEEP YOUR HANDS OFF MY LYRE.”

[1] James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion 1st edition 1890

☙

Report from High Commissioner of Police von Ferstl, March 1820 Concerning the stubborn and insulting behaviour evinced by Johann Senn, native of Pfunds in the Tyrol, on being arrested as one of the Freshmen Students' Association, on the occasion of the examination and confiscation of his papers carried out by regulation in his lodgings, during which he used the expressions, among others, that he "did not care a hang about the police," and further, that "the Government was too stupid to be able to penetrate into his secrets." It is also said that his friends, who were present, Schubert, the school assistant from the Rossau, and the law-student Streinsberg, as also the students who joined later, the undergraduate Zechenter from Cilli and the son of the wholesale dealer Bruchmann, law-student in the fourth year, chimed in against the authorized official in the same tone, inveighing against him with insulting and opprobrious language. The High Commissioner of Police reports this officially, in order that the excessive and reprehensible behaviour of the aforesaid may be suitably punished. The Chief Constable observes that this report will be taken into consideration during the proceedings against Senn; moreover, those individuals who have conducted themselves rudely towards the High Commissioner of Police during their visit to Senn will be called and severely reprimanded, and at the same time the Court Secretary Streinsberg as well as the wholesale dealer Bruchmann will be informed of their sons' conduct. From O.E. Deutsch (translated by Eric Blom), Schubert. A Documentary Biography London 1946 pp. 161 - 162

☙

Schubert’s source was Bruchmann’s manuscript.