Song of a seafarer to the Dioscuri (Gemini)

(Poet's title: Lied eines Schiffers an die Dioskuren)

Set by Schubert:

D 360

[1816]

Dioskuren, Zwillingssterne,

Die ihr leuchtet meinem Nachen,

Mich beruhigt auf dem Meere

Eure Milde, euer Wachen.

Wer auch, fest in sich begründet,

Unverzagt dem Sturm begegnet,

Fühlt sich doch in euren Strahlen

Doppelt mutig und gesegnet.

Dieses Ruder, das ich schwinge,

Meeresfluten zu zerteilen,

Hänge ich, so ich geborgen,

Auf an eures Tempels Säulen.

Castor and Pollux, twin stars,

You who light up my boat,

Calming me on the water

With your gentleness, your watchfulness.

No matter how self-confident someone is,

Even if they are not disheartened when encountering a storm,

In the rays of your light they will feel

Doubly courageous and blessed.

This oar that I manipulate

To separate the waters of the ocean,

Once I am safe I shall hang it

Up on the columns of your temple.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Boats Castor and Pollux Columns Courage Floods and tides On the water – rowing and sailing Prayers and praying Rays of light The sea Ships Stars Storms Temples Twins

Castor and Polydeuces (later Latinized to Pollux) appear in a number of Greek writers as the sons of Leda and her husband Tyndareus (or possibly Zeus). They are the brothers of Helen. By Roman times their temples had become associated with sailors, and they were looked to as protectors. In Catullus 4 the poet relates the journeys of an old ship and reports that it is now retired and dedicated ‘to you twin Castor and to Castor’s twin’ (dedicat tibi gemelle Castor et gemelle Castoris). In Pliny’s Natural History (2.37) there is an attempt at an explanation of why the constellation Gemini is so significant for mariners:

Stars also come into existence at sea and on land. I have seen a radiance of star-like appearance clinging to the javelins of soldiers on sentry duty at night in front of the rampart; and on a voyage stars alight on the yards and other parts of the ship, with a sound resembling a voice, hopping from perch to perch in the manner of birds. These when they come singly are disastrously heavy and wreck ships, and if they fall into the hold burn them up. If there are two of them, they denote safety and portend a successful voyage; and their approach is said to put to flight the terrible star called Helena: for this reason they are called Castor and Pollux, and people pray to them as gods for aid at sea. They also shine round men's heads at evening time; this is a great portent. All these things admit of no certain explanation; they are hidden away in the grandeur of nature. (English translation H. Rackham, Harvard University Press, 1949 - 1954)

Since Pliny wrote this in 77 CE, physicists have produced an explanation of the phenomenon (corona discharge or ‘St. Elmo’s fire’). The glow that can affect ships is indeed related to starlight, since it is plasma. Ships’ masts can operate as lightning conductors and set up electric fields that ionize the gas around them. The reliance on the constellation Gemini as protection from this threatening glow is less easy to explain in rational terms, though. Plasma physicists remain dubious about the suggestion that two discharges might be safer than a single one, so the idea of relying on twin stars for protection seems to be no more than mariners’ superstition.

We should not forget, though, how familiar sailors would have been with the night sky. Particularly in the ancient world, they would have had unrestricted views and the lack of ambient light would have helped them detect many more stars than we can see with the naked eye today. Most of them would have been involved in using the stars for navigation, so a knowledge of the constellations and of specific stars was a basic requirement for survival. It is hardly surprising that sailors wanted to feel a special connection with particular stars, and why shouldn’t they choose a celestial pair of twins as their protectors? Since they seemed to be attached to each other and they kept a lookout for each other, they were well placed to look out for those in peril on the seas.

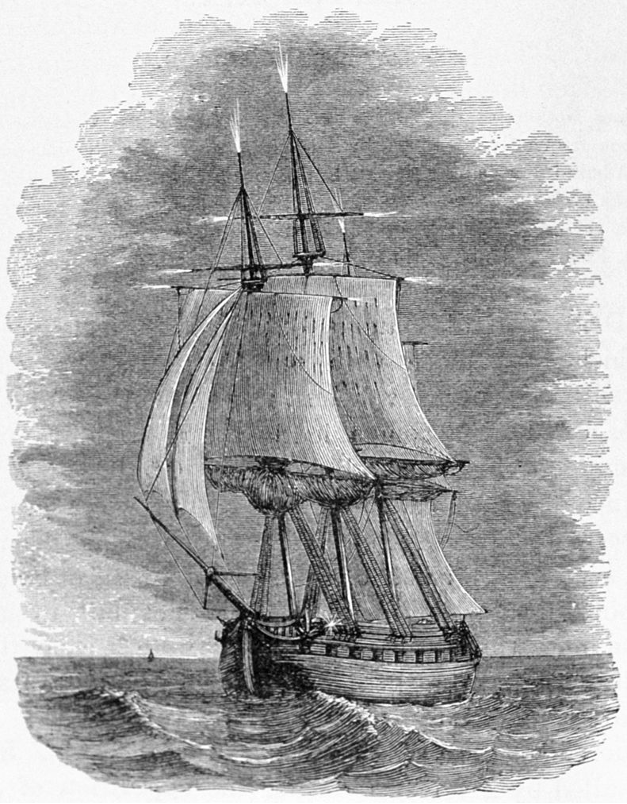

‘corbita’ from north Africa (found at Carthage), c. 200 CE

Note how the oar could also be a rudder (Mayrhofer’s ‘Ruder’ could be either). It is definitely ‘cutting’ the waters.

☙

Original Spelling Lied eines Schiffers an die Dioskuren Dioskuren, Zwillingssterne, Die ihr leuchtet meinem Nachen, Mich beruhigt auf dem Meere Eure Milde, euer Wachen. Wer auch fest in sich begründet, Unverzagt dem Sturm begegnet; Fühlt sich doch in euren Strahlen Doppelt muthig und gesegnet. Dieses Ruder, das ich schwinge, Meeresfluthen zu zertheilen; Hänge ich, so ich geborgen, Auf an eures Tempels Säulen.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 183.

Note: Schubert received Mayrhofer’s texts in manuscript; the manuscripts of his cycle Heliopolis, dedicated to Franz von Schober, are preserved in the Vienna City Library. The printed edition of Mayrhofer’s poems appeared much later. This poem (originally no. 20 of the cycle) is not part of the cycle in the printed edition of 1843.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 183 [197 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902