Unter den Linden

☙

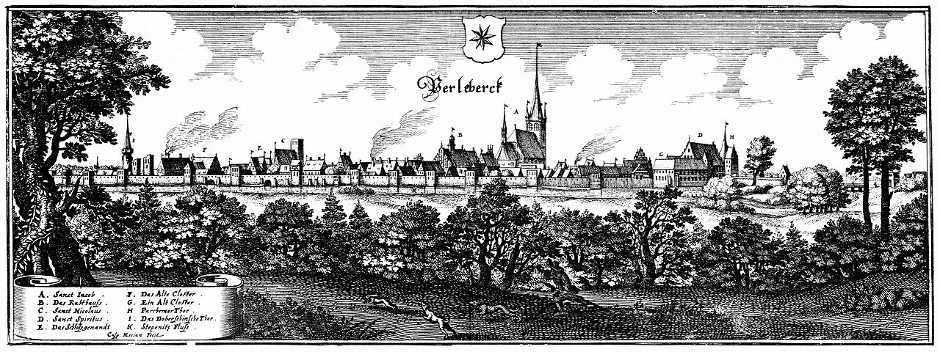

Having escaped to California from the Nazis, the singer Lotte Lehmann (1888 – 1976) looked back on her career and considered what it was to be German. She remembered the contrast between ordinary village life (being ‘deutsch’, with a small ‘d’ – homely, down to earth, straightforward) and the shock of moving to Berlin, the capital of the ‘Second Reich’, the capital of Deutschland (with a capital ‘D’). In her memoirs she commented on the contrast between the lime-trees of ‘Unter den Linden’ and her own beloved ‘Dorflinden’ (village limes) back in Perleberg:

I tried as hard as I could to feel “towny,” heroically suppressed any longings for the beautiful forsaken paradise of our garden, and overcame my disappointment at my first sight of the Tiergarten, where, instead of animals, as I had expected, I saw cars and electric trains. How I marvelled at “Unter den Linden,” that broad West-end boulevard! But I regarded with a mixture of scorn and sympathy the lime-trees which gave the beautiful street its name – miserable, stunted, insignificant. How I longed for the old lime-trees in Perleberg – “at home,” I thought with a heavy heart . . . .

Lotte Lehmann, Wings of Song. An Autobiography. London 1938 (translated by Margaret Ludwig) Chapter 3 (pp.23-24)

She cannot help but associate lime-trees both with home and with loss. This tone of nostalgia and sadness pervades most of the poems Schubert set to music which feature Linden trees.

Home and domesticity are evoked explicitly in ‘Alinde’ (D 904), a poem by Rochlitz that revolves around finding a lost love, in this case a woman whose very name rhymes with (and includes) the Linden tree:

Die Sonne sinkt ins tiefe Meer,

Da wollte sie kommen.

Geruhig trabt der Schnitter einher,

Mir ist's beklommen.

Hast, Schnitter, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde!

»Zu Weib und Kindern muss ich gehn,

Kann nicht nach andern Dirnen sehn;

Sie warten mein unter der Linde.«

The sun is setting into the deep sea,

She was going to come here.

A harvester calmly trots along,

I feel apprehensive.

Harvester, have you not seen my beloved?

Alinda! Alinda!

"I have to go to my wife and children,

I can't be looking for other lasses;

They are waiting for me under the lime tree."

Caroline Pichler, in ‘Ferne von der großen Stadt’ (D 483), expresses a longing for a rural retreat away from the pressures of city life, and central to her nostalgic vision of security is the lime-tree:

Freuden, die die Ruhe beut, Will ich ungestört hier schmecken, Hier, wo Bäume mich bedecken Und die Linde Duft verstreut. The joys offered by peacefulness Are what I am going to taste here undisturbed, Here, where trees offer me a roof And the lime tree emits fragrance.

For other writers, though, the sense of loss and longing is more explicit: the lime-tree is associated with the dead. Kosegarten in ‘Abends unter der Linde’ (D 235, D 237) feels that he communes with his dead children when he sits under the lime at night. Similarly Klopstock in ‘Die Sommernacht’ (D 289) thinks of his departed beloved as he smells the linden blossom in the moonlight:

Wenn der Schimmer von dem Monde nun herab In die Wälder sich ergießt, und Gerüche Mit den Düften von der Linde In den Kühlungen wehn, So umschatten mich Gedanken an das Grab Meiner Geliebten! When the gleam from the moon comes down now As it is poured into the woods, and fragrances With the smell of lime trees Waft into the cool breezes: Then it is that I am overshadowed by thoughts of the grave Of my beloved

In Engelhardt’s ‘Ihr Grab’ (D 736) the widower’s wife’s grave is actually under the lime-tree (which reminds us both of the happy domestic scene evoked in ‘Alinde’ and the fact that Werther asked to be buried under a lime tree in Goethe’s famous novel):

Dort ist ihr Grab - Dort schläft sie unter jener Linde, Ach, nimmer ich ihn wiederfinde Den Trost, den sie mir gab. Her grave is over there - She is sleeping over there, under that lime tree. Oh! I shall never find it again That comfort that she gave me!

Of course, the beloved does not always have to be dead to be missed:

Entblättert steht der Erlenhain, Entlaubt der traute Garten, Wo Er und ich im Mondenschein Einander bang erharrten; Wo Er und ich im Mondenblitz, Im Schirm der Linde saßen, Und auf des Rasens weichem Sitz Der öden Welt vergaßen The grove of alders finds itself stripped of its leaves, The familiar garden has lost its leaves, Where, in the moonshine, he and I Anxiously used to wait for each other; Where, in shafts of moonlight, he and I Would sit under the canopy of the lime tree, And on the soft seat of the lawn We forgot the bleak world. Kosegarten, 'Idens Schwanenlied' D 317

Geuß, lieber Mond, geuß deine Silberflimmer Durch dieses Buchengrün, Wo Phantasien und Traumgestalten immer Vor mir vorüber fliehn. Enthülle dich, dass ich die Stätte finde, Wo oft mein Mädchen saß, Und oft, im Wehn des Buchbaums und der Linde, Der goldnen Stadt vergaß. Pour, dear moon, pour your silver shimmering Through this green of the beech trees, Where fantasies and dream-forms always Fly past me! Reveal yourself, so that I can find the place Where my girl often sat And often, in the sighing of the beech and lime trees, Forgot the golden town! Hölty, 'An den Mond' D 193

A few of the poems Schubert selected to set focus on a happier time of love under the limes. Mayrhofer portrays a lover meeting ‘Liane’ (D 298), who arrives on a boat at her favourite place:

Die Linde spannt ihr grünes Netz, Aus Rosen tönt des Bachs Geschwätz, Die Blätter rötet Sonnengold, Und Alles ist der Freude hold. The lime tree stretches out its green net, The brook's prattling sounds out from amongst the roses, The gold of the sun makes the leaves red, And everything becomes beauteous with joy.

Müller’s winter traveller associates lime-trees in blossom with the eyes of the lost beloved (‘Rückblick’, D 911/8):

Wie anders hast du mich empfangen, Du Stadt der Unbeständigkeit, An deinen blanken Fenstern sangen Die Lerch und Nachtigall im Streit. Die runden Lindenbäume blühten, Die klaren Rinnen rauschten hell, Und, ach, zwei Mädchenaugen glühten, Da war's geschehn um dich, Gesell. How differently you received me, You town of inconstancy! At your shiny windows there was a song Competition between the larks and the nightingales. The round lime trees were in blossom, The clear channels of water were burbling brightly, And oh, a girl's two eyes were glowing! - That all happened because of you, my friend!

Matthisson’s ‘Stimme der Liebe’ (D 187, D 418) includes the old trope of the nightingale summoning lovers to a tryst under a lime-tree:

Abendgewölke schweben hell Am bepurpurten Himmel; Hesperus schaut mit Liebesblick Durch den blühenden Lindenhain, Und sein prophetisches Trauerlied Zirpt im Kraute das Heimchen! Freuden der Liebe harren dein! Flüstern leise die Winde; Freuden der Liebe harren dein! Tönt die Kehle der Nachtigall; Hoch von dem Sternengewölb herab Hallt mir die Stimme der Liebe! Evening clouds are floating brightly In the crimsoned sky. Hesperus is peering with a loving look Through the blossoming grove of lime trees, And the prophetic mourning song of The cricket is being chirped in the undergrowth! The joys of love are waiting for you! The winds are whispering softly; The joys of love are waiting for you! The throat of the nightingale is ringing out; High up in the vault of the stars The voice of love is echoing to me!

Such texts take us back to perhaps the most famous song from medieval Germany, Walther von der Vogelweide’s ‘Unter der linden’:

Under der linden

an der heide

dâ unser zweier bette was

dâ muget ir vinden

schône beide

gebrochen bluomen unde gras

vor dem walde in einem tal!

Tandaradei

schône sanc diu nahtegal.

Ich kam gegangen

zuo der ouwe

dô was mîn friedel komen ê.

Dâ wart ich empfangen

hêre frouwe,

daz ich bin sælic iemer mê!

Kust er mich? Wol tûsentstunt!

tandaradei

seht wie rôt mir ist der munt!

Dô hete er gemachet

alsô rîche

von bluomen eine bettestat;

des wirt noch gelachet

inneclîche

kumt iemen an daz selbe pfat.

Bî den rôsen er wol mac -

tandaradei

merken wâ mirz houbet lac!

Daz er bî mir læge

wesse ez iemen

nu enwelle got so schamte ich mich,

wes er mit mir pflæge

niemer niemen

bevinde daz wan er und ich.

Und ein kleinez vogellîn -

tandaradei

daz mac wol getriuwe sîn!

Under the linden

by the meadow,

where our bed was,

there you can find,

beautifully broken,

the flowers and the grass.

Before the forest in a valley--

Tandaradei--

Beautifully sang the nightingale.

I came walking

to the meadow,

my lover had come there already before.

There I was received,

(Holy Virgin!)

for that I am happy forever.

Did he kiss me? At least a thousand times.

tandaradei--

See, how red my mouth is!

There he made--

so splendidly,

a bed out of flowers.

Those will laugh,

heartily,

who come by on the path

and see by the roses,

tandaradei--

where my head lay.

That he lay with me--

if anyone knew

(God forbid) I would be ashamed.

How he was with me,

Never, no one

may find out, except for him and me,

and a little bird

tandaradei--

that will well keep my secret.

English translation (from Middle High German) by Elisabeth Siekhaus

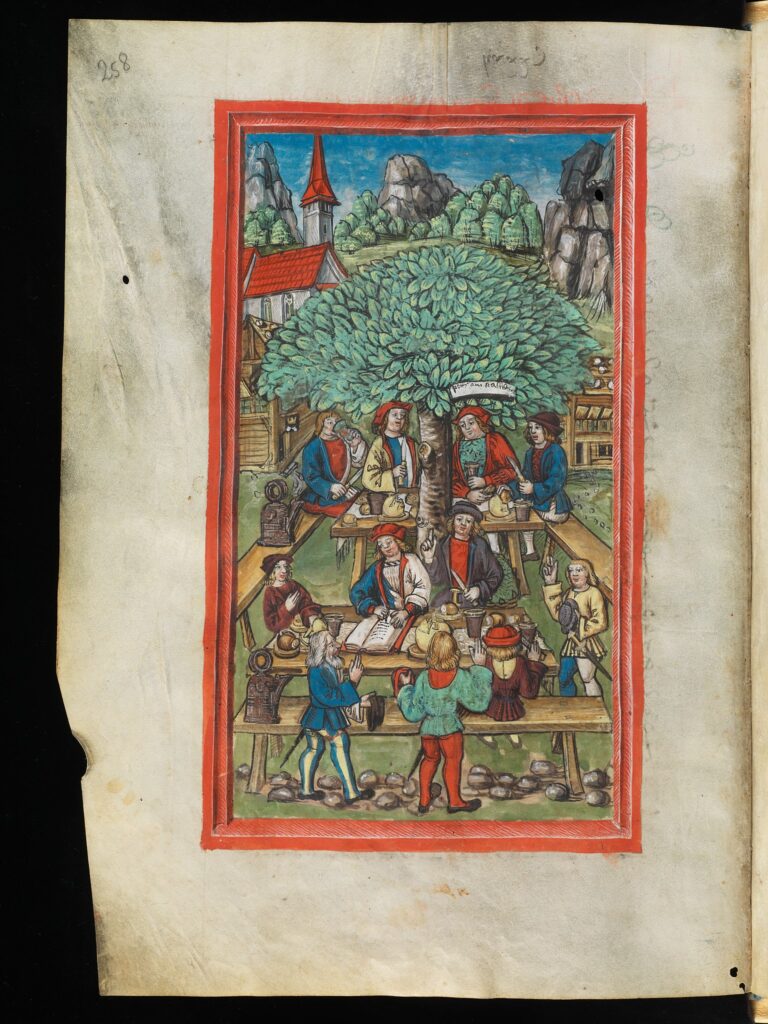

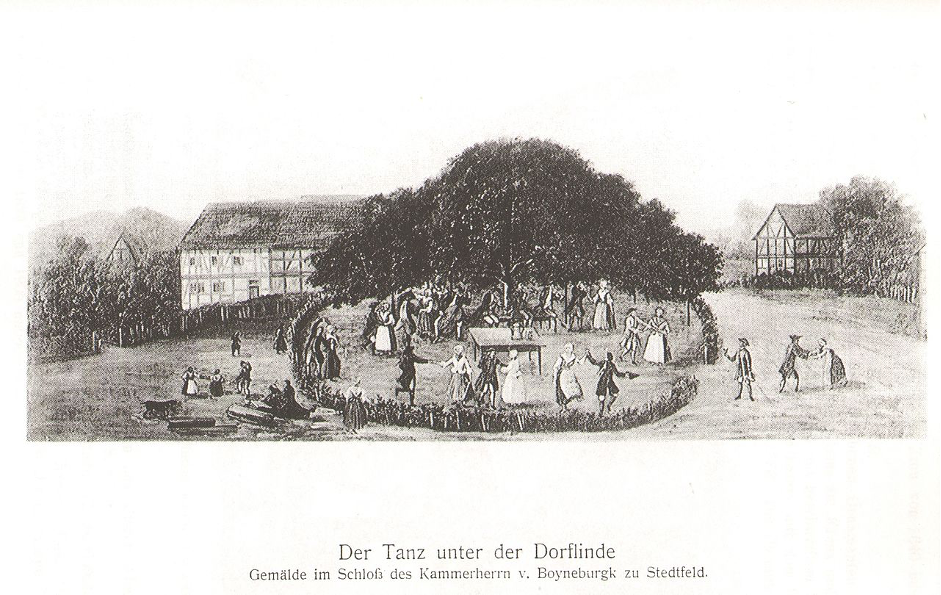

Despite the reference to the Virgin this text gives the impression that the lime-tree was a site of spring-time fertility rites. Such rituals appear to have survived ‘paganism’ and continued in later German customs in the form of ‘May dancing’, often with lime-trees serving as Maypoles, as can be seen in this etching from 18th century Eisenach (Bach’s birthplace!).

The lime functions as a Maypole in at least two of Schubert’s texts:

Denn wie ich bei der Linde Das junge Völkchen finde, Sogleich erreg ich sie. Der stumpfe Bursche bläht sich, Das steife Mädchen dreht sich Nach meiner Melodie. For when I am by the lime tree and I find young people I immediately arouse them. The down to earth lad swells up, The stiff lass spins around Following my melody. Goethe, 'Der Musensohn' D 764

Hüpft geschwinde Um die Linde, Die uns gelbe Blüten streut. Lasst uns frohe Lieder singen, Ketten schlingen, Wo man traut die Hand sich beut. Also schweben Wir durchs Leben, Leicht wie Rosenblätter hin. An den Jüngling, dunkelt's bänger, Schließt sich enger Seine traute Nachbarin. Leap quickly Around the lime tree That is strewing yellow blossom over us. Let us sing merry songs, Let us tie ourselves in chains As we intimately offer each other our hand. In this way we float Through life, Moving on lightly like rose petals. She approaches the young man as it gets darker and her anxiety grows, She attaches herself more closely to him - His devoted neighbour. Salis-Seewis, 'Zum Rundetanz' D 983B

What does a lime-tree mean, though, when May is over and the blossom has fallen? As we have already seen, it functions primarily as a reminder of loss and decay, as an enduring focus for nostalgia:

Sie hüpfte mit mir auf grünem Plan, Und sah die falbenden Linden an, Mit trauernden Kindesaugen. Die stillen Lauben sind entlaubt, Die Blumen hat der Herbst geraubt, Der Herbst will gar nichts taugen. Ach, du bist ein schönes Ding, Frühling! Über allen Zauber Frühling. She was jumping with me on the green expanses And she looked at the lime trees as they turned brown With the mournful eyes of a child; "The quiet foliage has fallen off, Autumn has stolen the flowers, Autumn has absolutely nothing to offer us. Oh, you are a beautiful thing, Spring! Above all magic - spring." Mayrhofer, 'Über allen Zauber Liebe' D 682

However, many people will simply take the bare lime-trees of winter for granted. They are so much part of the landscape and of village life that familiarity has bred contempt. They evoke no memories (of either pleasure or pain); they are simply there. The aristocratic poet Széchényi uses this fact to create an inverted nostalgia: looking forward from a time of happiness to a later time of loss and forgetfulness.

Wirst du halten, was du schwurst, Wenn mir die Zeit die Locken bleicht? Wie du über Berge fuhrst, Eilt das Wiedersehn nicht leicht. Ändrung ist das Kind der Zeit, Womit Trennung uns bedroht, Und was die Zukunft beut, Ist ein blässer's Lebensrot. Sieh, die Linde blühet noch, Als du heute von ihr gehst; Wirst sie wieder finden, doch Ihre Blüten stiehlt der West. Einsam steht sie dann, vorbei Geht man kalt, bemerkt sie kaum. Nur der Gärtner bleibt ihr treu, Denn er liebt in ihr den Baum. Will you stick to what you have sworn When time has bleached my hair? Since you are setting off over the mountains It is not going to be easy to rush to see each other again. Change is the child of time, Which separation threatens us with, And what the future holds Is a paler shade of life's red. Look, this lime tree is still in blossom As you depart from it today; When you come across it again, though, The westerly wind will have stolen its blossoms. It will then be standing on its own; as they pass by People will be cold and and will barely notice it. Only the gardener will remain faithful to it, For he loves the tree for its own sake. Széchényi, 'Die abgeblühte Linde' D 514

☙

Descendant of:

Plants and vegetationTexts with this theme:

- Stimme der Liebe, D 187, D 418 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- An den Mond (Geuß, lieber Mond), D 193 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Abends unter der Linde, D 235, D 237 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Sommernacht, D 289 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Liane, D 298 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Idens Schwanenlied, D 317 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Ritter Toggenburg, 397 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Herbstabend, D 405 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Lied (Ferne von der großen Stadt), D 483 (Caroline Pichler)

- Die abgeblühte Linde, D 514 (Ludwig (Lajos) Graf Széchényi von Sárvári-Felsö-Vidék)

- Über allen Zauber Liebe, D 682 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Ihr Grab, D 736 (Karl August Engelhardt)

- Der Musensohn, D 764 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Alinde, D 904 (Friedrich Rochlitz)

- Der Lindenbaum, D 911/5 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Rückblick, D 911/8 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Zum Rundetanz, D 983B, D Anh. I, 18 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)