The Wallenstein pikeman having a drink

(Poet's title: Der Wallensteiner Lanzknecht beim Trunk)

Set by Schubert:

D 931

[November 1827]

He! schenket mir im Helme ein,

Der ist des Knappen Becher,

Er ist nicht seicht und, traun, nicht klein,

Das freut den wackern Zecher.

Er schützte mich zu tausend Mal

Vor Kolben, Schwert und Spießen,

Er dient mir jetzt als Trinkpokal

Und in der Nacht als Kissen.

Vor Lützen traf ihn jüngst ein Speer,

Bin fast ins Gras gesunken,

Ja! wär er durch, hätt nimmermehr

Ein Tröpfelchen getrunken,

Doch kam’s nicht so. Ich danke dir,

Du brave Pickelhaube!

Der Schwede büßte bald dafür

Und röchelte im Staube.

Nu, tröst’ ihn Gott! Schenkt ein, schenkt ein,

Mein Krug hat tiefe Wunden,

Doch hält er noch den deutschen Wein

Und soll mir oft noch munden.

Hey, pour it into the helmet for me,

That is the beaker for a squire,

It is not shallow and, you have to admit, not small,

It cheers up the valiant drinker.

It has protected me a thousand times

Against clubs, swords and spears,

It is serving me now as a drinking vessel

And at night as a pillow.

At the battle of Lützen recently it met a spear,

I nearly sank into the grass,

Yes! if it had gone through – I would never

Have drunk another drop.

But it did not happen. I thank you,

Good old spiked helmet!

The Swede soon had to atone for that

And he bit the dust.

So, let God comfort him! Pour it out, pour it out!

There are deep wounds in my mug

But it can still hold German wine,

And I shall continue to enjoy it frequently.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Drinking songs Dust Germany and being German Grass Wine and vines

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Landsknecht_with_his_Wife.jpg

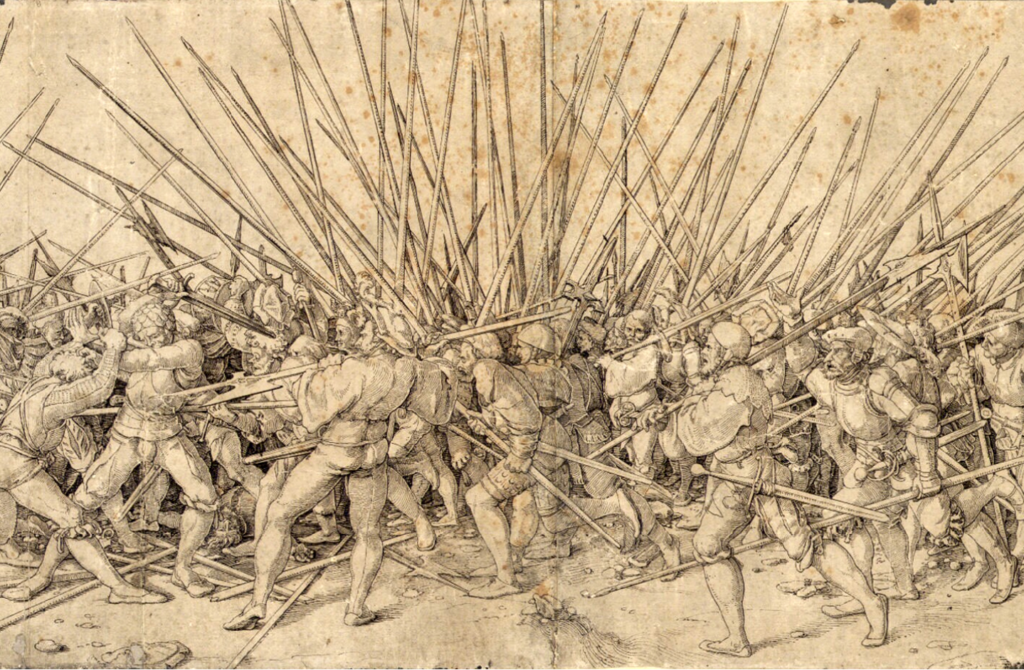

A ‘Lanzknecht’ was not really a ‘lancer’. His ‘Lanz’ was a pike or a spear and he was not on horseback. In any case, the word is a corruption of the original ‘Landsknecht’, a fighter supporting his ‘land’ or region. They fought in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly in the 16th century and by the beginning of the 17th century troops of them were available as mercenaries. This particular Lanzsknecht is part of the company of Albrecht von Wallenstein (1583 – 1634), who led a powerful private army, usually (but not totally reliably) in the service of the Habsburg Emperor.

This drinking song is clearly dated to just after the Battle of Lützen, which took place in November 1632. Wallenstein’s company was building on its success in the 1620s, when it had been central to the campaign of the Holy Roman Emperor to wrest control of the Kingdom of Bohemia away from the Protestants (and their supporters). Saxony was the next major field of conflict in this series of battles (which came to be called the Thirty Years War). If the Elector of Saxony could be defeated this would help to guarantee Habsburg control of the Empire and further the cause of the Counter-Reformation. Other Protestant Princes and states felt the need to support the Saxons, and outside powers were sucked in. The French (although nominally Catholic) were happy to support the King of Sweden’s intervention on behalf of his fellow Lutherans.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dankaerts-Historis-9360.tif

King Gustavus Adolphus was keen to lead from the front and has gone down in history as Sweden’s greatest military hero. His death at the aforementioned Battle of Lützen served to reinforce this reputation. If he had been defending the cause of Catholicism his status as a martyr would have been acknowledged more formally. It could well be that Leitner’s poem is intended to be in the voice of the ordinary German soldier who killed him. The soldier speaks of the Swede whose spear had nearly pierced his helmet dying shortly afterwards. In vivid, down-to-earth language he tells of how he heard the dying Swede’s death rattle in the dust (the literal meaning of ‘er röchelte im Staube’). At the same time he shows his pious Catholic upbringing by referring to the dying man’s penance or confession (a secondary meaning of ‘er büßte dafür’ – he atoned for it). No Lutheran would have accepted the use of the verb ‘büßen’ in this sense, of course.

Leitner’s soldier therefore typifies much of what later generations came to think about the Thirty Years War. What started out as a seemingly ideological dispute between Catholics and Protestants soon degenerated into a totally unprincipled grab for power (as much by generals like Wallenstein as different states, principalities, kings and emperors). Yet ordinary soldiers on different sides had more in common with each other than their superiors wanted to admit. Leitner’s Catholic soldier cannot stop himself from praying for the soul of the dead Swede that he killed (he probably has no awareness that Lutherans disapproved of praying for the dead). This appreciation of the common humanity of the combatants did a great deal to foster a more tolerant attitude to religious (and other) differences in northern and central Europe in the years that followed.

Leitner could have expected his original readers to be fully aware of all of this background. In 1813, only a few years before he wrote the text there had been a second Battle of Lützen, when the armies of Russia and Prussia engaged Napoleon in what Germans and Austrians later called the ‘War of Liberation’. All contemporaries hearing about this would have been reminded of the previous battle in the same place. Many people were also familiar with Schiller’s major dramatic trilogy on the career of Wallenstein (Wallensteins Lager, Die Piccolomini and Wallensteins Tod, 1798-99), so the title of the poem would not have looked as intimidating as it might to us. Needless to say, it would not have been difficult for anyone to sympathise with a man wanting a long drink at the end of the day.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_Scene,_after_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg

☙

Original Spelling Der Wallensteiner Lanzknecht beym Trunk He! schenket mir im Helme ein, Der ist des Knappen Becher, Er ist nicht seicht und, traun, nicht klein, Das freut den wackern Zecher. Er schützte mich zu tausend Mahl Vor Kolben, Schwert und Spießen, Er dient mir jetzt als Trinkpokal Und in der Nacht als Kissen. Vor Lützen traf ihn jüngst ein Speer, Bin fast in's Gras gesunken, Ja! wär' er durch, - hätt nimmermehr Ein Tröpfelchen getrunken. Doch kam's nicht so. Ich danke dir, Du brave Bickelhaube! Der Schwede büßte bald dafür, Und röchelte im Staube. Nu, tröst' ihn Gott! Schenkt ein, schenkt ein! Mein Krug hat tiefe Wunden, Doch hält er noch den deutschen Wein, Und soll mir oft noch munden.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Gedichte von Carl Gottfried Ritter von Leitner. Wien, gedruckt bey J. P. Sollinger. 1825, pages 17-18.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 17 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10113663